The Lay of the Case: Putting NZ Communication Design on the Map – Noel Waite

New Zealand can boast a varied and interesting design history that both reflects and diverges from international trends. However, this is very much an insider’s guide to design happiness, as many within the profession and most outside of it are unaware of this history because it has been so sporadically recorded. Currently, there are two major international histories of design that seek to broaden the scope of design history beyond the confines of North America and Europe, and it is imperative that New Zealand’s contributions are comprehensively recorded. This article will briefly summarise recent efforts to establish a global design history and attempt to establish a case for a history of communication design in New Zealand by outlining existing initiatives and examining the relevance of a strong bibliographic tradition of scholarship around New Zealand print culture. My goal here is simply to establish the lay of the case, rather than compose and set a definitive history, but my ultimate aim would be a functional design history that establishes local precedents and encourages designers to knowingly develop or subvert them.

However, before we reactively franchise the New Zealand operation to a corporate global narrative, it might be useful to revisit some of the questions posed by Australian design historian and critic Tony Fry in his 1988 book Design History Australia: A source text in methods and resources. He begins with a critical assessment of the major approaches to design history and seeks to develop a critical method appropriate to the Australian context. His own approach is explicitly located in post-structuralist theory and draws on contemporary cultural studies. He rejects a narrow focus on material objects and form and utopian attempts to create a universal narrative, arguing for a cultural history of formations and processes as a counter to an uncritical celebratory climate then prevalent in Australia. His aim was ‘to produce critical consciousness of how and why design operates’ (81), thereby encouraging greater design diversity and autonomy.

In New Zealand, a by-product of the Design Taskforce Report and Better by Design programme1 seems to be a similarly celebratory climate for design, admittedly with some good reason. However, the desire to develop and promote design as an economic driver and position New Zealand alongside similar-sized Scandinavian countries like Finland, Denmark and Sweden seems premised on a tenuous understanding of the different local contexts of production and consumption and their relationship to regional or global contexts. This is not to say that the comparisons are untenable or the ambitious goals—to generate an additional $500 million in export earnings in five years—are unrealisable, but that there is a considerable way to go before New Zealand achieves the depth of understanding of its own design history that exists in these countries or the active way they are promoted (such as the touring exhibitions ‘Celebrating 125 years of Finnish Design’ in 2003 and ‘From the Netherlands: Words & Images’ in 2005).

Three recent articles in the Journal of Design History set out, in Jonathan Woodham’s words, to ‘redraw the design historical map’ (257). Woodham critically examines the narrow geographical scope of most of the major design books—a gap that would come as no surprise to most design educators outside the major industrial nations. He then goes on to record the impact of four international Design History and Design Studies conferences held between 1999 and 2004 that set out to challenge the hegemony of design history which has been dominated by the output of major industrialized, consumer-oriented societies in Europe and North America. Woodham also noted concern from professional organizations like ICOGRADA (the International Council of Graphic Design Associations) about the loss of local or regional design narratives. The negative homogenizing aspects of globalization have renewed design students’ and professionals’ interest in learning about their own cultural context and history. The result is increasing recognition that an understanding of cultural difference is vital to developing effective and sustainable communications strategies in an increasingly international design environment. Woodham proposed a complementary partnership of theory and practice, with universities supporting professional organizations like ICOGRADA, ICSID (the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design) to research a more comprehensive and inclusive history of design. Brighton University’s Design History Research Unit, with its own archive (including the ICOGRADA poster collection) and links to the Brighton Museum collection of industrial design, certainly offers huge scope for a meaningful partnership of research, teaching and practice.

As the title of his article—‘A World History of Design and the History of the World’—suggests, Victor Margolin takes an even broader view. He argues that ‘a world history of design with an emphasis on how empires, nations, and other political entities have used it to advance their political and economic agendas links design to the larger problems of the world’ (235). He notes that the emergence of design history as a discrete discipline in the 1970s, and its breaking of ties with art history, owes much to the democratization of subject matter wrought by shifts in focus from political to social history and a broadening of interest from high culture to the everyday. However, he acknowledges the lingering influence of Pevsner’s and Giedion’s pioneering studies, both of which concerned modernisation and the consequences of industrialisation and emphasised objects over contexts. Margolin proposes shifting emphasis from the planning of objects for mass production to the conception and planning of material and visual culture in particular social, political and economic contexts.

However, it is Anna Calvera’s article that perhaps has the most relevance for a New Zealand audience. As one of the convenors of the First International Conference of Design History and Design Studies in Barcelona in 1999, she is passionate about recording Spain’s design history in all its regional variants as well as its particular mediations of international theories and practices. In her article, she proposes a geographical approach to the history of design that, by focusing on difference between national identities, may lead to new interpretive models that can, in turn, be adapted to local realities—the ‘feedback’ of her title. Her reconfigured map of design would ‘set aside the vertical axis of economic dependence as the main argument to portray the peripheral situation and try to balance the model focusing on those aspects that give originality to peripheral experiences in order to build up a map composed of equals’ (375).

Calvera also questions the value of determining the arrival of Modernism as definitive. If we are to turn to the New Zealand situation, Douglas Lloyd-Jenkins’ recent book of At Home in New Zealand is a valuable overview of design as related to its parent discipline of architecture. It reflects a turn to social history in its focus on the domestic environment (not to mention, in the fact of its publication, a public receptiveness to New Zealand design unthinkable 30 years ago). Its thesis on the dominance and acceptance of craft production is a particularly useful contribution to the debate about design history in this country, but its over-reliance on a nationalist myth of modernism infuses it with an art historical preoccupation with stylistic movements and heroic designers. In part this can be attributed to the familial linking of design with architecture. To avoid these pitfalls, Calvera suggests more fruitful avenues in determining how modern is determined in relation to existing craft traditions, or when and how the term design emerges in its own right.

Despite the theoretical strength of Tony Fry’s arguments mentioned earlier about the shift from object to context, even he chose to focus on industrial design in Australia with the attendant emphasis on industrialisation and modernisation suggested by Margolin. A more instructive example might be to examine the history of communication design in New Zealand. Admittedly, while much has recently been written on the history of graphic design, a good deal of it lacks the depth of analysis and methodologies developed with regard to industrial design (with one or two notable examples like Robin Kinross and Paul Jobling). However, if we accept Richard Buchanan’s assertion that communication is one of the defining aspects of design,2 this field seems in need of closer attention, particularly as New Zealand has a develop-ing body of contextual knowledge arising out of the History of Print Culture in New Zealand (HoPCiNZ) project.3

HoPCiNZ was established in 1997 as a joint initiative between the Alexander Turnbull Library and the Council for the Humanities and developed from international initiatives around national histories of the book. The Histoire du Livre originated in the renowned French Annales school under Lucien Febvre and Henri- Jean Martin, whose book, The Coming of the Book, led to multi-volume histories of the book in France, Britain and Australia among others.4 The ultimate aim of these projects was to more fully understand a world history of the circulation of books and knowledge. New Zealand’s first initiative was Griffith, Maslen & Harvey’s Book & Print in New Zealand, which set out to establish what was known about the field as well as the major research gaps. The adoption of the term ‘Print Culture’ signified a more egalitarian focus, (more in line with Fernand Braudel, another historian of the Annales school who pioneered the study of everyday life, and interested in world histories), as well as an acknowledgement of the Maori oral culture that preceded the colonial introduction of print. This was also in line with a strong sociological and partly materialist tradition that had been developed by New Zealand bibliographers, most notably Don McKenzie and Keith Maslen. A number of initiatives followed from this tentative mapping of the landscape, including Griffith, Hughes & Loney’s A Book in the Hand, seven national conferences and four Marsden grants. Of particular note was the Maori newspapers project which has proved to be a remarkable resource,5 but also offers considerable potential for research into design by Maori for Maori in the nineteenth century.

1835 (Redrawn from McKenzie, 24)

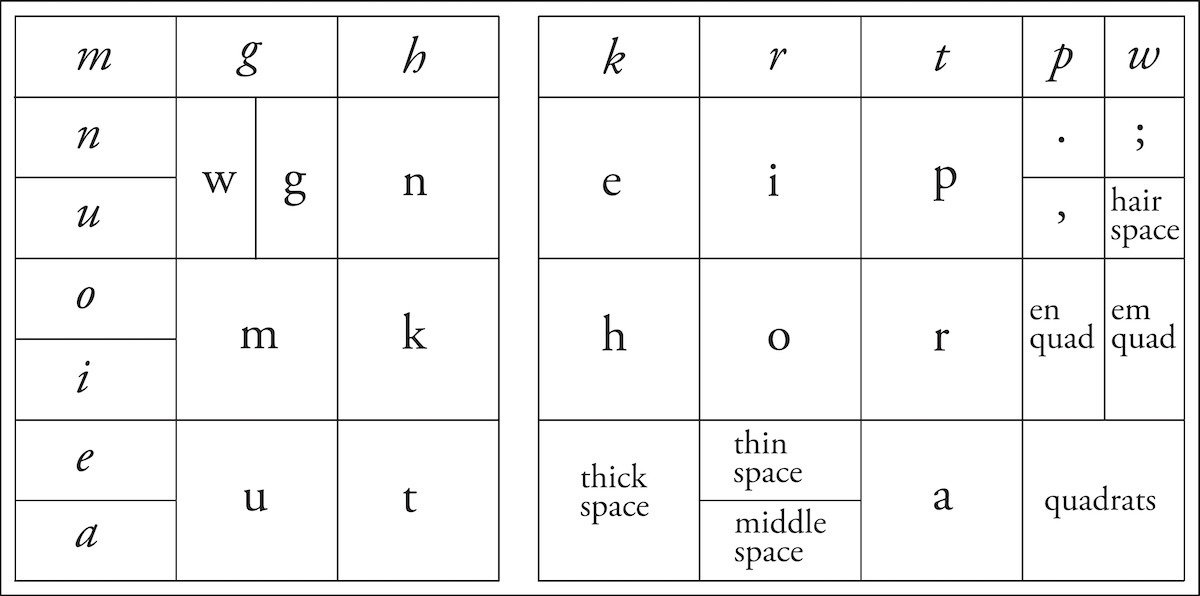

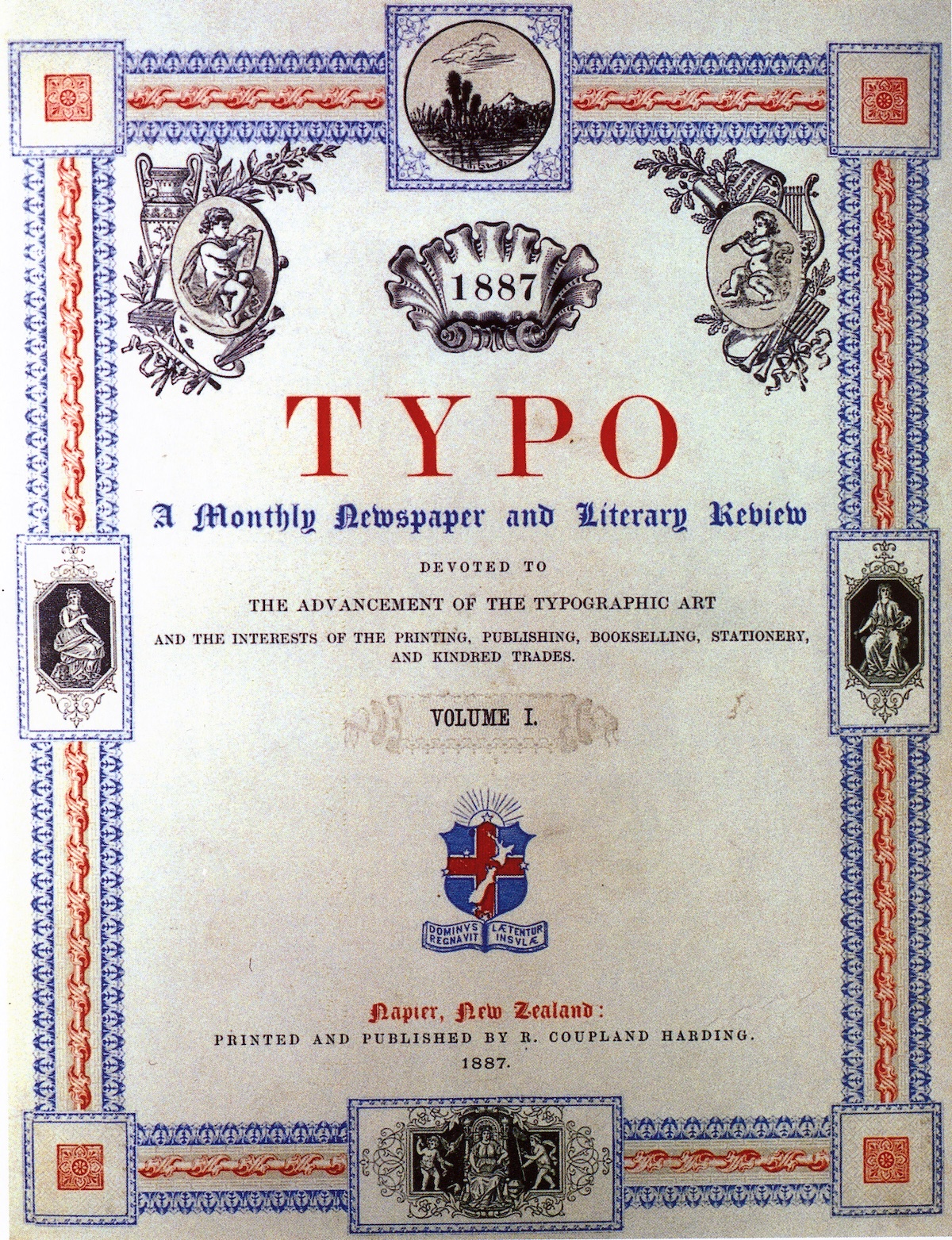

Like Fry’s book, Book & Print in New Zealand set out a list of available resources for further study and is a useful resource for a history of graphic design with its origins in the print industry. Missionary printer William Colenso’s redesigning of a type case to accommodate the particular orthography of the Maori language6 is but one example of design that admirably addresses the wider view espoused by Margolin (see fig. 1). Likewise Robert Coupland Harding’s7 outstanding international journal Typo (1887–97), provides a fantastic resource for nineteenth-century typographic design. His series of articles ‘Design and Typography’ were internationally syndicated and predate a general perception about the emergence of design in New Zealand and, with its references to, and synthesis of European, North & South American design, undermine linear colonial models of design influence (fig. 2).

(Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago)

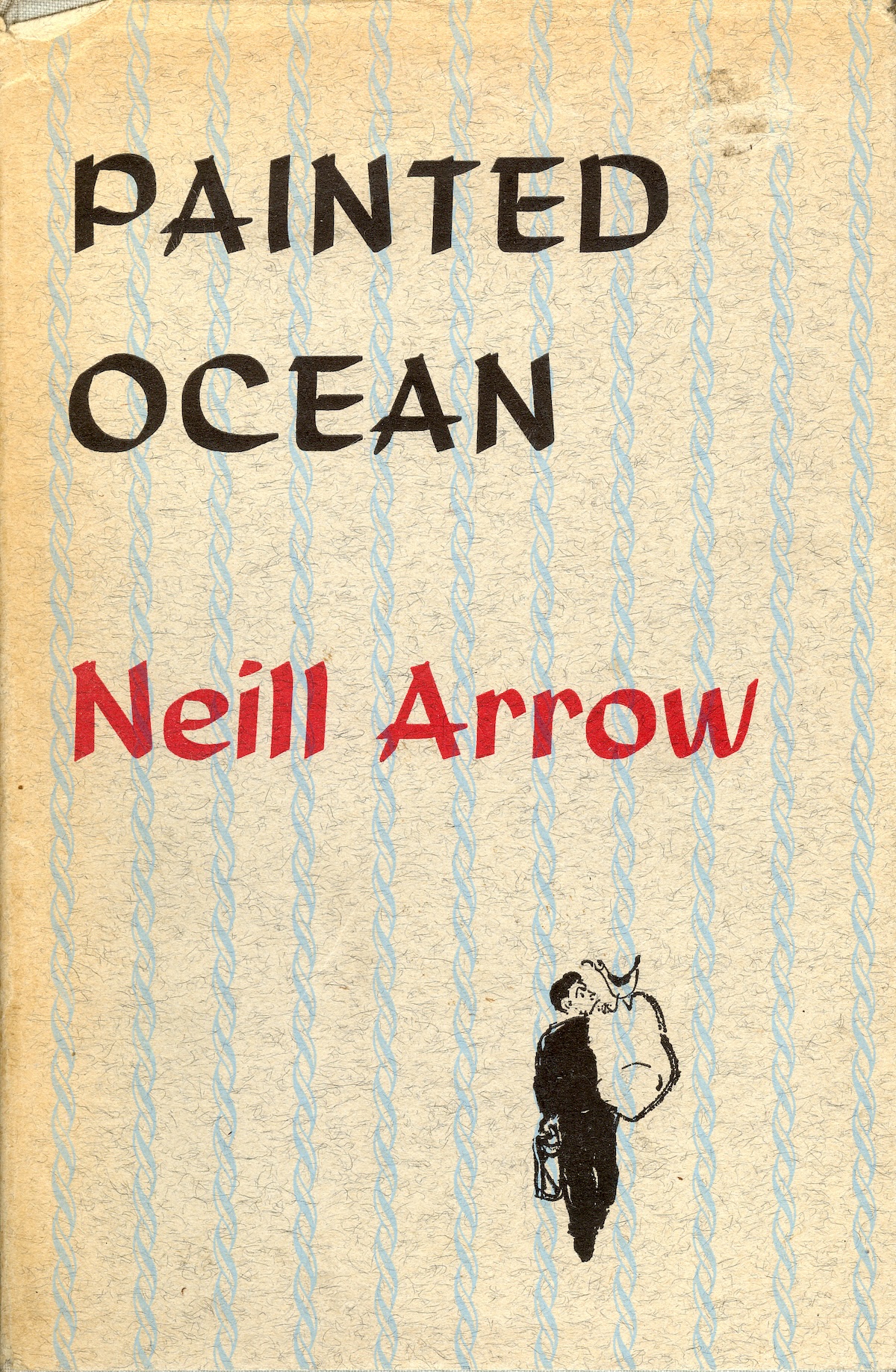

Owen Jones’ Grammar of Ornament (1856) opens with a sermon on the superiority of the ‘New-Zealander’s’ [read Maori] pattern-making skills. While the matter of industrial production conveniently—and conventionally—excludes precolonisation craft production, the question of what constitutes Maori design is a complex one that deserves considerable attention. Questions over whether particular hoahoa or patterns can be separated from the kaupapa of which they are a part is one for Maori scholars and relevant iwi to determine. It is an issue of particular relevance to the complex area of cultural appropriation and more specific recent developments in the area of intellectual property and the guardianship of cultural knowledge in a globalised market economy. This significantly affects communication design, from wine labels and sport promotion to tourism strategies and the design of our national flag. All of these topics would suggest many avenues for investigation about when design emerged in New Zealand and how it has been defined by its particular context. (fig. 3)

(Christchurch: Caxton Press, 1962)

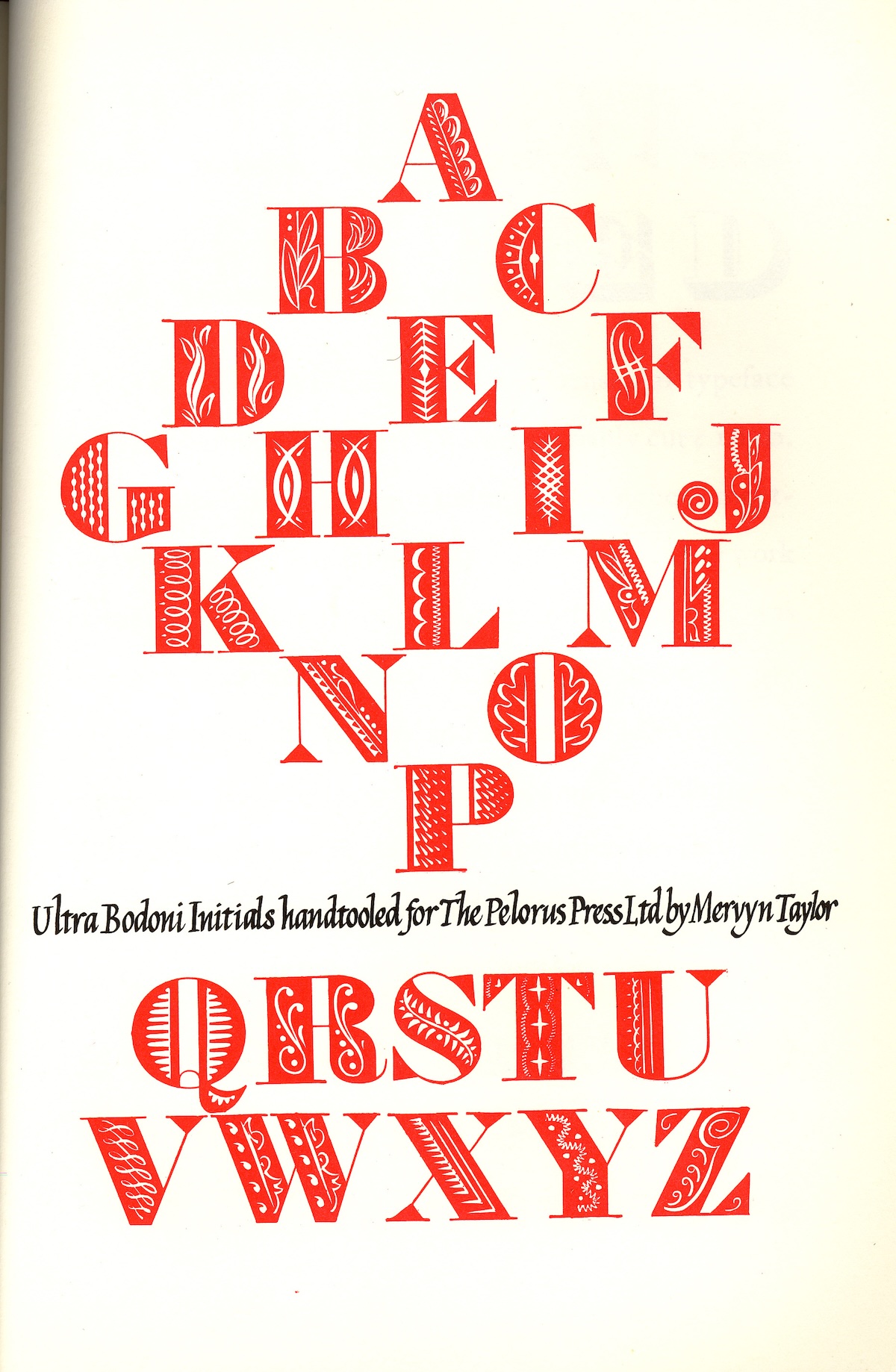

with illustration by Julia Faithful and jacket and book design by Leo Bensemann

Traditionally, design history has given precedence to product (3-dimensional) design because of its intimate connection with industrial production and the tangible evidence collected in museums. This approach has been increasingly criticised for its fetishisation of objects and lack of regard for production processes and the social and political context from which they arose (Buchanan 1989, Margolin 2002). Communication design encompasses visual communication in a variety of industrial media, where effectiveness is based on content, its relationship to context and audience engagement rather than simple aesthetic merit (Buchanan 1989 & 2001).8 This broader conception is more suited to critical analysis of the ways New Zealand has communicated with, and is communicated to the rest of the world. Topics covered could include industrial exhibitions, department store and museum display, signage, currency (including stamps), flags, books (see fig. 3), typography (see fig. 4 overleaf), illustration, newspapers and magazines, posters, packaging and advertising. These can be examined in terms of profiles of individual designers and companies, the cultural, educational and political organizations that contributed to design development in New Zealand, and the impact of technological change. Such a history of communication design in New Zealand would enable design students and professionals to develop a deeper understanding of their own cultural context and history, and would hopefully contribute to more effective and sustainable communications strategies in an increasingly international design environment. This is a necessary complement to the future-oriented aims of the Design Taskforce and Better by Design programme, which, as mentioned earlier, takes little account of the actively communicated design heritage of the most innovative countries that New Zealand is setting out to emulate, such as Finland, Denmark and the Netherlands.

c.1967

Mapping a New Zealand design history then presents itself as something of a wicked problem requiring a designerly approach to methodology and outcome. One of the key problems of developing a truly representative social history of design has been the breadth of subject matter encompassed by design. By defining the topic in terms of a national history in the field of communication design, where an industrialised print culture was imported almost fully fledged and dynamically engaged with an indigenous oral culture, there is an opportunity for a more encompassing design history to be developed in New Zealand. To avoid charges of parochialism, it would need to be followed by a comparative study with other national histories under the rubric of a world history.

Museums, archives and libraries, as well as private collections offer a wide and almost unrivalled spectrum of primary resources. Oral history is also a crucial methodology that has proved particularly fruitful in Design Studies at the University of Otago. This method enables an emphasis on design processes to complement an examination of design objects, as well as a means of capturing the unrecorded experience of more recent practitioners. It is also a versatile source material with regards to communicating design history in that it can be deployed in multimedia formats.9

It follows that the communication of such a design history should itself be carefully designed to be both visually and critically sophisticated. Critically, it would need to encompass the three approaches by Calvera, Woodham and Margolin outlined earlier. As Calvera noted, there is a fundamental need to document and research ‘peripheral’ national histories; Woodham’s Twentieth-Century Design offers a useful model for synchronic analysis; while Margolin’s synthesis of design issues into practice demands relevance without abandoning critical integrity. A central issue raised by Calvera is the importance of establishing a feedback loop between general and local histories, such that each informs the other and linear models of influence are displaced by a two-way directional flow. Just as HoPCiNZ’s outcomes have primarily been books in line with its origins in the Histoire du Livre, communication design’s egalitarian treatment of media would suggest a layered multimedia approach. Aside from offering greater scope for information design, it provides the most appropriate means to communicate to a variety of audiences— from general to educational (primary, secondary & tertiary) to professional—and to adequately represent the complexity of such research and the diversity of sources—material, oral, textual, visual, environmental—from which it originated.

The existing initiative of Auckland University of Technology’s New Zealand Design Archive (http:// www.nzda.ac.nz/) provides a useful central platform for publication, particularly if it could be developed to accommodate streaming media. Woodham, who is a Professor at the University of Brighton’s excellent Design History Research Centre, has noted the New Zealand initiative and concurs with Director Frances Joseph’s assessment that digital archiving technologies ‘will no doubt be important in developing strategies for the recovery of … currently invisible histories and the dissemination of research findings, documentary and visual evidence’ (265). Linking to the Government’s proposed Cultural Portal Project10 would also enhance international visibility. This would need to be complemented by book publication and journal articles, but would offer both a central outlet for design historical research as well as design opportunities for student and professional designers.

I conclude with two examples known to small communities of interest that warrant and would attract broader audiences if more widely known. Alice Lake-Hammond’s fourth-year Design Studies project involved interviewing Julia Faithful, a well known painter in Southland. This led her to curate and design an exhibition for the Riverton Community Art Centre on her commercial art in the 1960s and 1970s. Her research revealed a variety of work spanning book, magazine and newspaper illustration, fashion design, ticket writing and display design in department stores, corporate calendars and advertising. The project documented a transition phase from commercial art to graphic design, as well as a rare portrait of a female designer. The second example resulted from the publication of Hamish Thompson’s Paste Up: A Century of New Zealand Poster Art, a useful representative survey of the breadth of subject matter addressed by design. This proved to be invaluable source material and inspiration for an Auckland creative director to design an award-winning national brand.

The qualities necessary to undertake the kind of design history research outlined here—and adequately communicate it—are the dogged perseverance of the historian, the attention to detail of the bibliographer, the holistic and opportunistic vision of the designer, and the desire of the librarian to make knowledge accessible. Whether the New Zealand case lay is like the English, American or Spanish model, or more closely resembles William Colenso’s cultural hybrid will only be known as research is documented, disseminated and critically discussed in national and international contexts.

Footnotes

See http://www.betterbydesign.org.nz/ and http://www.nzte.govt.nz/section/13680.aspx ↵

See ‘Declaration by Design: Rhetoric, Argument, and Demonstration in Design Practice’, (91) ↵

See link at http://www.humanz.co.nz/ ↵

See links to national histories at http://www.sharpweb.org/

Closer to New Zealand, see Lyons & Arnold’s A History of the Book in Australia, the first of a three-volume history ↵

See ‘Niupepa: Maori Newspapers’, http://www.nzdl.org/cgi-bin/niupepalibrary?a= p&p=about&c=niupepa and Curnow, Hopa & McRae’s book Rere Atu Taku Manu! ↵

See reproduction at http://members.aol.com/typecases/mclcase.htm and in more detail in Don McKenzie’s Oral Culture, Literacy & Print in Early New Zealand, (22–25) ↵

Harding produced his remarkable journal from Napier and Wellington. See ‘Typo & Typothetae’ (21–25) in Waite’s ‘Printers’ Proof’ and Harding’s biography at http://www.dnzb.govt.nz/dnzb/ ↵

In ‘Design Research and the New Learning’, Buchanan argues ‘communication is the essence of this branch of design, independent of the medium in which communication is presented’ (10) ↵

Recent projects include oral histories of former employees of Railways Studios, a key Government design department concerned with tourism publicity, Southland-based commercial artist Julia Faithful, printers and a City Council architect. As well as texts, these have been communicated in the form of exhibitions, interpretive panels, CDs and websites (see ‘Printing in Otago 1950–2000’ http://www.intermundi.com/otago/eval.cfm) ↵

See http://www.digitalstrategy.govt.nz/templates/Page____121.aspx ↵

Reference List

Buchanan, Richard, ‘Declaration by Design: Rhetoric, Argument, and Demonstration in Design Practice’ in Design Discourse: History Theory Criticism, ed. Victor Margolin. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1989, (91–109).

——, ‘Design Research and the New Learning’ in Design Issues 17.4, 2001, (3–23).

Calvera, Anna, ‘Local, Regional, National, Global and Feedback: Several Issues To Be Faced With Constructing Regional Narratives’ Journal of Design History 18.4., (371–383).

Curnow, Jennifer, Ngapare Hopa and Jane McRae (eds.), Rere Atu Taku Manu! Discovering History, Language & Politics in the Māori Language Newspapers. Auckland: Auckland UP, 2002.

Febvre, Lucien and Henri-Jean Martin, The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing 1450–1800. London: Verso, 1990.

Fry, Tony, Design History Australia: A source text in methods and resources, Sydney: Hale & Iremonger & Power institute of Fine Arts, 1988.

Giedion, Sigfried, Mechanization Takes Command, A Contribution to Anonymous History. New York, Oxford UP, 1948.

Griffith, Penny, Keith Maslen and Ross Harvey (eds.), Book & Print in New Zealand: A Guide to Print Culture in Aotearoa. Wellington: Victoria UP, 1997.

——, Peter Hughes and Alan Loney (eds.), A Book in the Hand: Essays on the History of the Book in New Zealand Auckland: Auckland UP, 2000.

Jobling, Paul and David Crowley. Graphic Design: Reproduction and Representation Since 1800 Manchester: Manchester UP, 1996.

Jones, Owen, The Grammar of Ornament: Illustrated by Examples from Various Styles of Ornament. London: B. Quaritch, 1928.

Lloyd-Jenkins, Douglas, At Home: A Century of New Zealand Design. Glenfield: Godwit, 2004.

Lyons, Martyn and John Arnold (eds). A History of the Book in Australia, 1891–1945: A National Culture in a Colonised Market. St Lucia, Qld.: U of Queensland P, 2001.

Margolin, Victor, ‘Design History and Design Studies’ in The Politics of the Artificial: Essays on Design and Design Studies. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2002, (218–33).

——, ‘A World History of Design and the History of the World’ Journal of Design History 18.3., (235–243).

McKenzie, D.F., Oral Culture, Literacy & Print in Early New Zealand: The Treaty of Waitangi. Wellington: Victoria UP & Alexander Turnbull Library Endowment Trust, 1985.

Pevsner, Nikolaus, Pioneers of Modern Design: from William Morris to Walter Gropius. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1960.

Thompson, Hamish, Paste Up: A Century of New Zealand Poster Art. Auckland: Godwit, 2003.

Waite, Noel, ‘Printers’ Proof: The Dunedin Master Printers’ Association 1889–1894’, Bibliographical Society of Australia & New Zealand Bulletin (2001) 25: 1&2, (17– 42).

Woodham, Jonathan M., ‘Local, National and Global: Redrawing the Design Historical Map’ Journal of Design History 18.3., (257–267).

——, Twentieth Century Design Oxford: Oxford UP, 1997.