Counterfeit Design: A Tactical Approach – Luke Wood

‘Normally this issue, and the others, are unwatermarked,’ Cohen said, ‘and in view of other details—the hatching, number of perforations, way the paper has aged—it’s obviously a counterfeit. Not just an error.'

– Thomas Pynchon, The Crying of Lot 49

A Visit to The Printer

One morning in early December last year I made one of many trips to a local printer to check-up on the printing of this publications second issue. I’d already been there a number of times, gotten to know people, and could generally just stroll on into the large warehouse where the presses would be chugging away. This particular time however, I was stopped at reception and told I wouldn’t be able to see the job “on the press”. Initially I wasn’t told why, and of course I imagined the worst — bad printing. When someone eventually bought me a couple of samples and they looked perfectly acceptable, I asked why I hadn’t been allowed in. The person I asked said they didn’t know, but looked a little shifty or uncomfortable when answering.

I left, curious, assuming that there’d been some sort of accident perhaps, a mess that needed to be cleaned up? Later that same day I returned to check another sheet as it passed through the press. I went into the reception area and waited around, but was surprised to be told to “just go on in”. This time there were some alterations to be made, and eventually someone from upper-management became involved. When the issue was resolved and I was on my way out I made a point of asking the upper-management type fellow what had been going on earlier. Immediately I got the same sort of shifty glance that I’d noticed earlier, but this time I got an answer too — stamps.

I didn’t get much more information than that, but basically our printer was employed by the government to print postal stamps, and when such a job was on, the building was under tight security and lock-down. I’d never really thought about it before, that printing stamps was sort of very much like printing money, but the experience triggered a memory…

A few weeks earlier I’d heard something on the radio about a graphic designer from Auckland being convicted for some sort of fraud relating to counterfeit documents. I remember thinking I should buy a newspaper and get the full story, but I never got around to it and by a couple of weeks later I’d forgotten all about it. Until this visit to the printer that is. Since then these two vaguely related incidents have sat somewhere in the back of my mind, refusing to go away, and looking for some sort of extra significance.

The Curious Case of Rebecca Li

In November 2006 Rebecca Li was sentenced to four years in prison, having been found guilty on 49 charges of forgery; counterfeit tertiary degrees, birth certificates, language school diplomas, corporate seals, immigration stamps, tax invoices, driver licenses, and disability permits. And, it seems, she was pretty good at it—the court referring to a phony Auckland University degree as a “magnificent fake”.1

Li set up her advertising and design company, Reddix Productions, in the Grey Lynn suburb of Auckland in 1997. During the following seven years, with a small number of different employees, the studio engaged in apparently legitimate work alongside its “business of commercial, professional, detailed crime”.2 Li’s more subversive services were advertised by word-of- mouth, or through discreet placements in The Mandarin Times, and she is believed to have charged about $1500 for a university degree, although these were often sold through a middle-man who was free to add his own mark-up. A fake driver’s license was surprisingly affordable at $300, whereas on the other hand a phoney IELTS (English Language) certificate could cost around $5000.3

Rebecca Li denied all charges, claiming ignorance and blaming dishonest ‘rogue’ employees. However, based on evidence that employees were hired on a temporary basis, with few staying more than a couple of weeks or months, the prosecution maintained that Li was in fact a major player in organised professional forgery here in New Zealand.

“What was going on here was a commercial forgery business, and here are the tools of the trade,” he said, brandishing bundles of high-quality paper.4

What interested me most at the time was the neat illustration of exactly how reliant we still are on hardcopy documentation, on pieces of paper with things printed, written, and/or stuck on them. As a graphic designer it’s hard not to be at least a little seduced by the craft, if not the politics and possibility of this kind of deception. Interestingly enough it turns out that Li actually has a degree—a real one—in Computer Science from Auckland University, and during the trial a former detective involved in the case pointed to Li’s “in-depth knowledge of computers and programmes” as some sort of hard evidence against her.5 Of course I couldn’t help thinking about the proliferation of design schools in New Zealand over recent years, and the exponentially increasing number of people who possess similar such ‘in-depth knowledge’.

To Counterfeit is Death

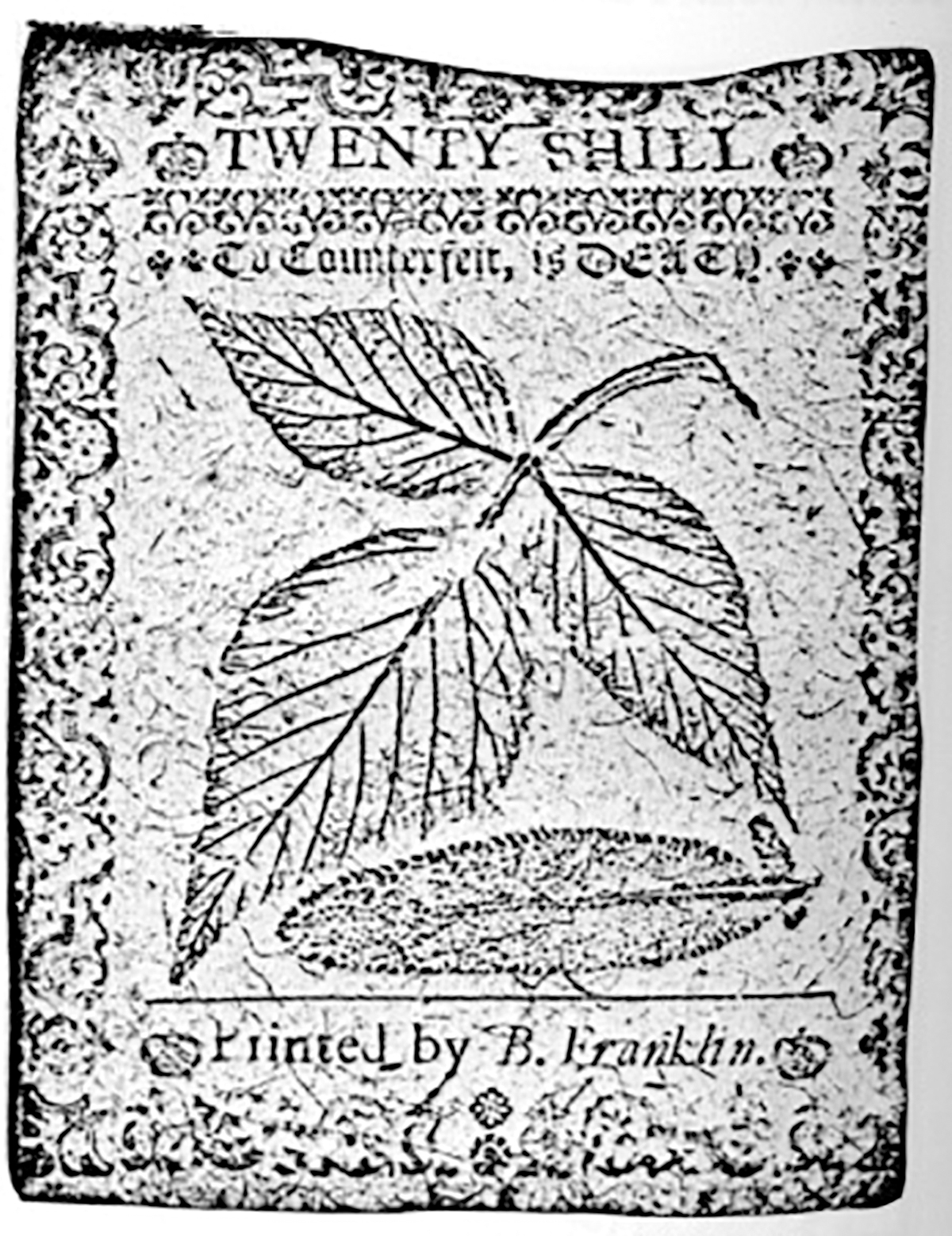

Most popular accounts of counterfeiting usually revolve around identity fraud, art, or money. Counterfeit money is as old as cash itself, and up until the end of the 18th Century men were hanged, drawn, and quartered, and women were burnt alive when convicted on charges of counterfeiting or money tampering.6 The extreme nature of the punishment was justified by the implication of ‘treason’ over and above simple crime—anyone with the skills to counterfeit currency represented a serious threat to the safety and stability of The State. Benjamin Franklin printed it—very plainly—on early American paper currency... “to counterfeit is death”.

Economies are fragile, mutable systems, and the impact of unauthorised ‘money’ entering the system can result in the reduction in value of real money, and potentially rapid inflation. For exactly this reason warring nations, or states, have attempted to use counterfeiting as a means of destabilising enemy economies. One well known—although failed—example is ‘Operation Bernhard’, Nazi Germany’s production of English pounds during WWII. In 1942 prisoners at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp were put to work engraving the complex printing plates, developing the appropriate rag-based paper with correct watermarks, and establishing the code to generate valid serial numbers. This work proved time consuming and difficult, though by the time Sachsenhausen was evacuated due to the rapid advance of Allied soldiers in April 1945, the printing press there had produced 8,965,080 banknotes with a total value of £134,610,810. Most of the counterfeit currency was abandoned however, dumped in Lake Toplitz by the retreating German army. The loot was recovered by divers in 1959, but examples continued to turn up in circulation in Britain for many years.

Such potential creates fertile ground for governmental paranoia and state sponsored conspiracy theories, reciprocally the finest counterfeit money in circulation today is supposed to be based on the American dollar. ‘Superdollars’, as they are called, are printed using both intaglio and offset printing processes, often with higher quality inks and paper than their authentic cousins. Officially known as the PN-14342 notes, they reproduce the various security features of United States currency so well that even trained experts must study a note intensively before determining if it is indeed a fake. They are claimed, by the U.S. government, to be coming out of North Korea—to finance the Communist government there and to destabilise the ‘free’ American economy—although this has never been satisfactorily proven, and North Korea claims that it is a fabrication of the United States, issued as a pretext to war.

Of course this sort of large-scale project, while sharing a name, is light years away from the example I’m interested in here. Initially please note that Rebecca Li wasn’t making large amounts of money from her work,7 nor—more importantly—was she actively trying to undermine or overthrow the institutions whose documents she was forging. She was, for all intents and purposes, simply ‘getting by’. And I know that might sound silly here, but I want to try and look at the Rebecca Li case as being not just a petty small-time version of these grander and more complex stories above, but as something quite fundamentally different.

Strategies and Tactics

Around about the same time as the trip to the printer I was telling you about before, a visiting friend accidentally left a book at my house. It sat on my kitchen table for a good month or so—its academic text book looking cover and the author’s ‘French theory’ type name keeping it quite safe from my summer holiday attitude. Eventually though—too much coffee and the poetic title perhaps—I got around to taking a look...

In his book The Practice of Everyday Life (1974), Michel de Certeau sets out to articulate and examine various ways in which individuals subvert and ‘make habitable’ the rules, rituals, and representations that institutions (political, religious, corporate, academic, and so on) seek to impose upon them. He repositions the usually docile and passive ‘consumer’ as an active and engaged ‘user’, and in doing so sets up the act of consumption as a sort of secondary form of production—one often hidden in the process of utilisation. Consumption, according to de Certeau, is “devious, it is dispersed, but it insinuates itself everywhere, silently and almost invisibly, because it does not manifest itself through its own products, but rather through its ways of using the products imposed by a dominant economic order”.8 What I’m getting at here is that I don’t think it’s too much of leap to suggest that something of the same spirit exists in the work of Rebecca Li. Let me see if I can explain.

Central to The Practice of Everyday Life is the theme of resistance, and in particular how the ‘weak’ make use of the ‘strong’. This practical distinction is characterised through two different forms of operational logic appropriated from a military context—institutions in general are described as ‘strategic’ and individuals (everyday people, non-producers) as ‘tactical’.

Strategy is the operational logic of authority, of organised or sanctioned groups, of producers, and of the elite. It is top down, and it manifests itself in its sites of operation (offices, headquarters) and in its products (laws, language, rituals, art, commercial goods). Its goal is to perpetuate itself through these things it makes, and so in the interests of efficiency it requires uniformity, systemisation, and order. Its ways are set, and a strategy tends to be inflexible because it is bound in space (buildings, assests) and time (its own history, traditions). It cannot, therefore, reorganise quickly or easily.

Tactical operations, on the other hand, are dispersed in space and time—having no specific site of operation and being makeshift, or based on the necessity of the moment. Many common, everyday practices are described by de Certeau, as being tactical in nature—“talking, reading, moving about, shopping, cooking, etc.” A tactic then manifests itself as a methodology rather than a product. It is flexible. It can break up and regroup intuitively as it responds to need (whereas strategy aims to create need), and will often make use of loopholes, relying on “clever tricks, knowing how to get away with things”.9

Not to be confused with guerrilla warfare or terrorism, de Certeau points out that where the tactics of the everyday seek to infiltrate they do not engage in sabotage, or other sorts of attempts to undermine, or to over-throw the framework they operate within (or against). To do so would be strategic of course. He emphasises that, alert to its status as the weak, the intention of a tactic is not to take a strategy on, but simply to fulfil its needs behind an appearance of conformity.

And so back to Rebecca Li, whose work was predominantly produced for, and within, an immigrant community—a generally disempowered community attempting to ‘get by’ within a steady barrage of foreign strategies. The appropriation of military terminologies by de Certeau serves to illustrate the battle of everyday life, and where the law is one thing, the complexity of real human interactions is another. When de Certeau talks about “making do”10 he is referring to an operational logic for survival that is practically instinctual, and—for my purposes at least—the art of the tactical counterfeiter serves as a good example of this idea in practice.

Opposition Masquerading as Allegiance

Somewhere in between the everyday tactics of Rebecca Li’s misdemeanour and the strategic complexity of the Superdollar lies Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, and his fictional account of the Tristero; an underground postal network ‘uncovered’ by protagonist Oedipa Maas when she is called upon to execute the will of a former lover—a wealthy Californian real-estate mogul with a stamp collection. While the initial discovery is made via a toilet wall, counterfeit stamps provide much of the evidence for the fictional history lesson, and what starts out looking like some sort of dodgy inter-office mail delivery service soon blossoms into a complex conspiracy theory that crosses 500 years and the Atlantic Ocean. While we learn that in its initial incarnation in the fourteenth century the Tristero was a more ‘strategic’ operation, employing violent means against rival European mail couriers Thurn and Taxis, by the time we meet them via Oedipa’s encounters in California in the late 1960s, the organisation seems to have more in common with the tactical operations of de Certeau. The shift in operational logic occurs, almost precisely, when the shadowy figures of Tristero adherents arrive as immigrants in America…

"While the Pony Express is defying deserts, savages and sidewinders, Tristero’s giving its employees crash courses in Siouan and Athapascan dialects. Disguised as Indians their messengers mosey westward. Reach the coast everytime, zero attrition rate, not a scratch on them. Their entire emphasis now towards silence, impersonation, opposition masquerading as allegiance."

They do not aim to bring-down, or go-up-against, the monopoly of the US postal service. The Tristero (and their customers)11 aim to simultaneously reject and infiltrate the strategy/production of the state, while all the time hidden, quietly within a cloak of conformity.12

"It was not an act of treason, nor possibly even defiance. But it was a calculated withdrawal, from the life of the Republic, from its machinery. Whatever else was being denied them out of hate, indifference to the power of their vote, loopholes, simple ignorance, this withdrawal was their own, unpublicised, private. Since they could not have withdrawn into a vacuum (could they?), there had to exist the separate, silent, unsuspected world."

As a mode of resistance this is perhaps too organised for the everyday tactics that de Certeau describes, and, of course, the Tristero network must be a form of production in itself (although we never hear of any centralised HQ). But in its preference for invisibility, silence, and impersonation it shares some of the qualities, or spirit, that I like about Rebecca Li’s work. The difference here though is a sort of extension of the brief…

"'The question is, who did these? They’re atrocious.’ He flipped the stamp over and with the tip of the tweezers showed her. The picture had a Pony Express rider galloping out of a western fort. From Shrubbery over on the righthand side and possibly in the direction the rider would be heading, protruded a single, painstakingly engraved, black feather. ‘Why put in a deliberate mistake?’ he asked, ignoring—if he saw it—the look on her face. ‘I’ve come up so far with eight in all. Each one has an error like this, laboriously worked into the design, like a taunt. There’s even a transposition—US Potsage, of all things.’"

Where, for obvious reasons, a counterfeiter will aim for as close a reproduction as possible, the Tristero forgeries delight in jocuserious misbehaviour, illustrating how little notice we actually take of the ephemeral forms and documents that overwhelm our everyday experience.

"In the 15c dark green from the 1893 Columbian Exposition Issue (‘Columbus Announcing His Discovery’), the faces of the three courtiers, receiving the news at the right hand side of the stamp, had been subtly altered to express uncontrollable fright."13

And so...

Returning to my trip to the printer—and I suppose we’ve taken the long way around—I can’t help romantically imagining that someone in pre-press might have slipped some small and practically imperceptible ‘modification’ into one of those stamps. Perhaps I’m not taking this seriously enough though—in January this year $150,000 worth of counterfeit NZ Post stamps were seized at Auckland’s International Mail Centre.14 And while I’m quite plainly romanticising the work of Rebecca Li via these two books I just happened to be reading, I certainly do not mean to advocate fraud.

But it does seem like there might be a whole genre of graphic design... that has nothing at all to do with originality, innovation or style, but is refreshingly common and ephemeral—more specifically interested in systems, relational structures and networks of distribution, than objects, artefacts and aesthetics. Concerned with ‘making do’, with helping people to get the most out of what’s been made available to them.

As long as graphic design has been around its practitioners have fretted over its development as a tool of social and political resistance. Perhaps what emerges is, in reality, much more insidious and potently pragmatic than the signatories of the First Things First manifesto15 have imagined.

Footnotes

David Eames, ‘Phoney degree ‘magnificent fake’ court told’, New Zealand Herald, Thursday October 5, 2006. ↵

Ibid. ↵

David Eames, ‘Conviction caps major play in dud NZ degrees’, New Zealand Herald, Saturday October 14, 2006. ↵

David Eames quoting Crown prosecutor Bruce Northwood, ‘Jury out today in fake degree case’, New Zealand Herald, Thursday October 12, 2006. ↵

David Eames quoting former Asian Crime Squad Detective Jimmy Jin, ‘Conviction caps major play in dud NZ degrees’, New Zealand Herald,Saturday October 14, 2006. ↵

Shaving or ‘clipping’ the edges of coins was common when they were made from gold or silver, and this carried the same penalty as counterfeiting. ↵

In court her brother testified that while she was financially sound and had no outstanding debts, her studio was a mess, she didn’t wear a lot of jewellery, and she didn’t spend a lot of money. ↵

Michel de Certeau, from the ‘General Introduction’ to Steven Rendall’s translation of The Practice of Everyday Life, Berkeley: University of California Press 1988 (originally published in French, 1974). ↵

Ibid. ↵

Chapter three is called ‘“Making Do”: Uses and Tactics’. I like his use of that term, similar to ‘getting by’ it sounds as speculative and abstract as the behaviour it represents actually is. ↵

No mention is ever really made of ‘payment’, and the impression is that of some sort of ‘gift economy’—another important aspect of de Certeau’s ideas about tactics. ↵

A similar sort of masquerading as official culture by American hard-core bands in the 1980s has been discussed by Mark Owens in his piece ‘Graphics Incognito’ in Dot Dot Dot 12. In (last-minute) hindsight I think this piece might have been quite influential here. ↵

Thomas Pynchon, The Crying of Lot 49, Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 1999 (first published 1966). ↵

Press Release: New Zealand Customs Service, Thursday 1 February 2007,11:32 am. http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PO0702/S00005.htm ↵

First Things First manifesto, orginally published in 1964 by Ken Garland and signed by over 400 graphic designers and artists. Anti-consumerism and anti-advertising in its stance, the manifesto proposed a “reversal of priorities in favour of the more useful and more lasting forms of communication”. The manifesto was updated and republished by Adbusters in 2000, and the position against advertising and marketing was made even more explicit. The authors yearn for “pursuits more worthy”, although it never really articulates what these are. I presume they mean non-rhetorical, functional projects like bus tickets and airport signage systems? Max Bruinsma’s website is worth visiting if you want to know more (http://www.xs4all.nl/~maxb/ftf2000.htm). ↵