An extraordinary denial of history – Noel Waite

Report and strategic plan

The Design Taskforce Industry New Zealand

Wellington

2003

Richard Buchanan has suggested that design has evolved from craft, to profession, to discipline in the 20th century, but in reading Success by Design (2003), one could be forgiven for thinking that the discipline had bypassed New Zealand. As Christopher Thompson argued in The National Grid #6 the document perpetuates “an extraordinary denial of history”1 and “its associated discipline of theory”.2

The fundamental disciplinary basis of history, criticism and theory —or look backwards, look around and look forward, as I suggest to my students—is a necessary complement to any kind of engaged, participatory and activist design within and from New Zealand. Re-reading this document with 10 years’ hindsight advantage, I am struck by the turn-of-the-century/millennium optimism, and the sense in which the document is informed by a bullish optimism about the potential for design. However, the positivist reduction to the synergistic formula “5 x 50 x 500 x 5” also reminds me of late 19th-century boosterism as the mechanical production processes and products of the industrial revolution were unleashed on an aspirational consumer class.

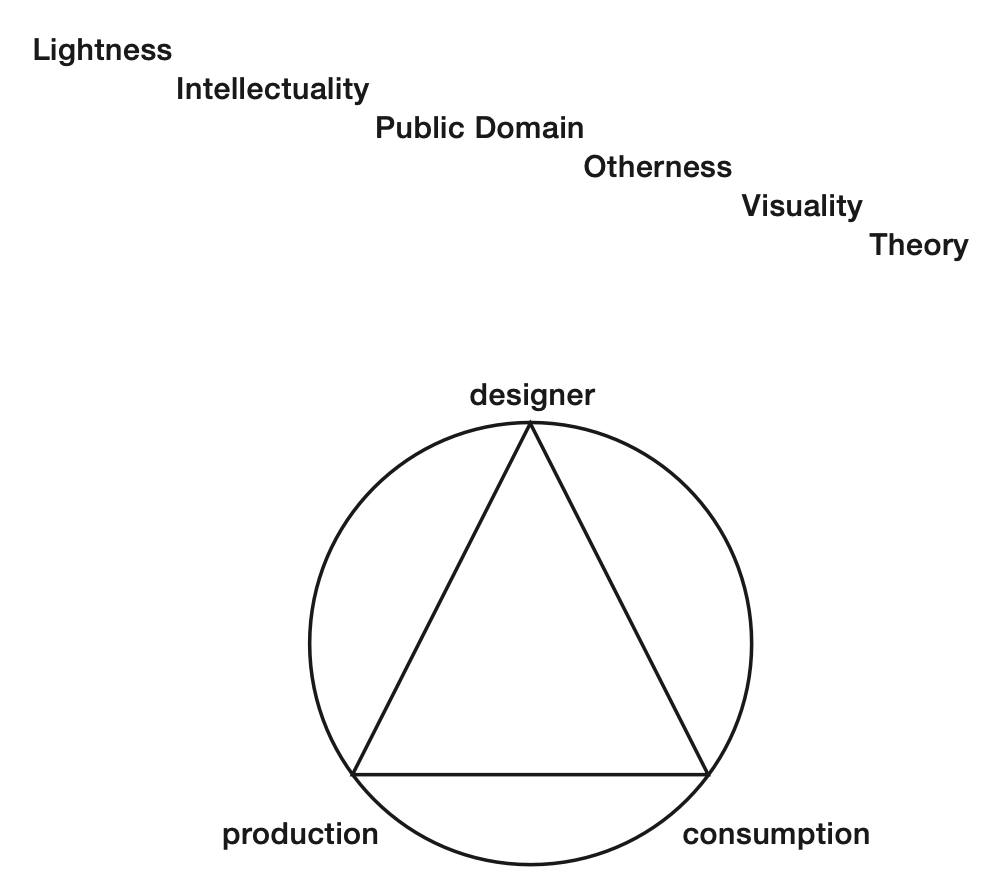

Thompson compellingly argues that the production focus of this document reduces consumers to a passive role within a neoliberal market economy premised on exchange value rather than use or need. Guy Julier’s critical tripartite model of design culture, viewed as a dial, would waver between the design profession and production in measuring this document, and the circle would be government patronage. Of course, Julier’s model was an attempt to map the designer’s role as a bridge between production and consumption, and the most challenging opportunities for designers lie in new modes of distribution, and the embodiment of ethical values responsive to a post-industrial society and glocal awareness.

Design culture + the cultural heritage of design

Leaving aside the narrow 20th-century focus on product and communication design (excluding the new fields, or ‘orders’ of interaction, systems and experience design) and the re-creation of a professional design brand and identity, it is perhaps helpful to reconsider the Supporting cultural Mission and Objective (37) of the Strategic Framework. Here, the emphasis (albeit briefly) is on the cultural significance of design and the key role played by compulsory secondary education. As Thompson points out, there is little in this document for anyone interested in the diverse and successful history of design in Aotearoa New Zealand (and certainly no mention of its weaknesses or failures). While the NZIDC is mentioned in a vague and cursory way (7.2 Appendix 2 Glossary of Terms), there is a sense in which the design profession has learned a valuable historical lesson from the NZIDC by focussing on the profession rather than manufacturing. However, the focus of the case studies on product design obscures the demonstrable success of communication design, in particular book publishing and creative advertising.

Design research + the science of design

This cultural heritage is only sporadically before the public and is largely disaggregated (TNG #6, with Michael Smythe’s new book a notable exception). The mission to have all New Zealanders valuing excellence in New Zealand design requires a more coordinated effort to try to bring it before national and international audiences. It also requires acknowledgement of the supportive, as well as activist and critical role of design in terms of cultural, national and international identities of New Zealand.

This cultural mission is also undercut by the research focus on applied and experimental development (28), suggesting that fundamental research into and for design can be deferred, or imported, while the profession focusses on quantitative targets that appear unsustainable from within the current recessionary global context. The remarkable history of fundamental scientific research resulting in innovative applied science from New Zealand, and the business imperative to invest in research & development when the economy slows suggest that a failure to prioritise fundamental research is a significant weakness.

A second important inter-disciplinary (and political) shift is the increasing emphasis on a science of design and working in inter- disciplinary teams on the ‘wicked’ problems facing New Zealand and all nations. The present Government’s focus on science and innovation, and developments within the secondary Technology curriculum have the potential to make up for this significant deficit in Success by Design, but even the current political drivers suggest an uncoordinated and ad hoc approach to design—a form of political #8 wire.

Finland, Finland, Finland

Pekka Korvenmaa’s Finnish Design provides a useful model for a rich social and cultural history of design, but Success by Design’s singular and simplistic (land mass + population) comparisons with a country like Finland seem tenuous and not in line with a synthesis of diverse, fit-for-purpose overseas best practice inflected locally. Looking more broadly to participatory innovation models from Scandinavia, Denmark in particular, the socially democratic Dutch activist approach to communication design, and the Italian model of distributed national production and culturally and theoretically engaged design offer other interesting opportunities for New Zealand design to develop in sustaining ways.

Closer to home, Tony Fry’s book Design Futuring poses a radical challenge to all designers to contribute to what he terms the Sustainment. The main contributing editor of the Design Philosophy Papers, who wrote an excellent critical history of Australian design in 1988, has hit his straps, and his renovation of an ethos of craft—care and attention to materials—aligns with Donald Schon’s formulation of design as a reflective practice.

Success by Design clearly constitutes an important, if stuttering step in the development of the New Zealand design profession, but more fundamental research will be needed if design is to fulfill its promise to New Zealand, and the design values laid out by Gui Bonsiepe (interviewed in ProDesign in 2004):