Pegasus Town's Model Life – Harold Grieves

Pegasus Town is to be a new satellite town built specifically to create a self-sustaining community for the North Canterbury region of New Zealand’s South Island. Scheduled for completion at the turn of the next decade, it is currently being receptively pitched as a unique mixture of resort-style atmosphere and community focused, small town, civility. Loosely based on a model of New Urbanism, in which self-sustaining communities are emphasised through the combination of mixed density dwelling and the promotion of open space environments that invite pedestrian comfort and community interaction by restricting vehicle access, the Pegasus Town developer, Infinity Investment Group, is hoping to create ‘not a satellite suburb’ but an ‘authentic Canterbury town’.1 Appealing to a traditional New Zealand identity, Infinity Investment Group base this quintessential enclave of middleclass desire around a lifestyle ‘that offers all the benefits of one of the best locations in the South Island’.2 Central to this proposal is an explicit communitarian ethic that prides itself on the contemporary isolation of the modern consumer who is over-determined by what Mathew Hyland has called the pre-emptive transformation of life itself into durational labour.3 This conflation is one of the central aspects of Pegasus Town’s promotion of a universalised ideal that explicitly links leisure with lifestyle. Encapsulated by the Pegasus Town slogan, ‘live where you play’, Pegasus Town is underwritten by a leisure economy which seeks to attract an idealised citizen whose working lifestyle is conflated with leisure rather than alienated from it.

Infinity Investment Group’s promotion of Pegasus Town has deliberately idealised their preferred residents as ‘the traditional Kiwi family’.4 Taking as their generational cue the ‘simple, uncomplicated’ architectural style that has ‘evolved to make the most of the landscape and the importance of the outdoor environment’,5 Infinity Investment Group make a direct appeal to a ‘North Canterbury vernacular’ that has developed in direct relationship to the region’s 19th century migration of northern hemisphere populations.6 Enlisting an everyman sensibility whose signifying attribute is the development of a ‘unique lifestyle’ in which ‘entertainment and recreation are built into the very fabric of the community’.7 This traditionalism quickly becomes short hand for an idealised embodiment of a laissez-faire ethic which holds leisure and ease to be the universalised component of a ‘town that values a sense of identity, of neighbourhood, of open access and shared enjoyment’.8 Perhaps, more clearly though, Infinity Investment Group’s idealisation of the traditional Kiwi family can be seen in their C.E.O. Bob Roberston. As a member of the Business Round Table and an active supporter of the National Party it is hard not to read Robertson’s traditionalised sentiments outside of the divisive, ‘mainstream’ ploys used by the National Party in the 2005 New Zealand election.9 Even more telling, is Robertson’s claim that he treats himself as Pegasus Town’s ‘guinea pig’ and that its model life ‘is based on what I would want’.10

Pinning their hopes specifically on the familial quest for the quiet life, the Pegasus Town vision deliberately evokes an aspirational lifestyle. Central to this is the town’s orientation as a satellite enclave which will be removed from a crasser, more fragmented world. Just as Andrew Ross has noted of the marketing for Disney’s own New Urbanist development, Celebration in Osceola, Florida, Pegasus Town’s pitch is created to highlight the limited and conditional opportunities currently available within the Canterbury region.11 The notable ingredient in this aspirational speculation is Pegasus Town’s compositional form in which it is promoted as a ‘vision’ that ‘encapsulates the very best of what this country and region have to offer’.12 This can easily be seen in the promotional billboards for Pegasus Town, which deliberately emphasised the exceptional range of leisure options readily available to the Pegasus Town citizen. Whether it is serene kayakers paddling through idealised wetland environments or smiling children riding ponies, Pegasus Town’s implicit draw card is its centralised range of leisure activities that are all within easy access to its citizens but almost too impossibly diversified under the current conditions of Christchurch’s suburban disparities. Thus, the happy images of children running across soccer fields to get to school, or the sedate romantic charm of two adults enjoying the leisure and ease of cafe- style dining, are deliberate promotional appeals that contrast with the fragmented reality of Christchurch which requires at least a half hour drive across town to simply go from urban café to wetland reserve. Through such registers Pegasus Town’s wilful slogan, ‘live where you play’ is a deliberate appeal to the disaffected consumers of Christchurch’s diffuse recreational and domestic segregations. In doing this, Pegasus Town’s promotional pitch triggers the underlying impulse of suburban sprawl itself, which as Robert Bruegmann has shown, is intimately linked to the democratisation of the opportunities and privilege that were once reserved for an elite few. Arguing that suburban sprawl is driven by the need for ‘privacy, mobility, and choice’, Bruegmann has shown how the proliferation of suburbia corresponds to the increasing per capita wealth of a nation.13 Pointing out that the original suburban impulse were the exurban country houses and retreats of the privileged few, Bruegmann has argued that the condescension surrounding suburbs is little more than snobbery based on self-entitlement. Bruegmann’s Christchurch counterpart, Hugh Pavletich, similarly advocates the democratic principle of suburbia. Arguing against the restriction of suburban development through policies that encourage urban regeneration and consolidation, Palevitch argues that the restrictions which currently curb suburban growth, ‘strangle Christchurch and inflate prices, so that people in average-paying jobs cannot afford to live here’.14 Pegasus Town’s deliberate promotion of a centralised leisure economy and its universalising of the ideal family unit slips all too easily into this niche of self-serving entitlement whilst preserving a façade of democratic opportunity.

Central to the unifying vision of Pegasus Town’s economy of leisure is the creation of a 35 acre, man-made lake. Pitched perfectly as an Aquatic Playground, Pegasus Lake is the focal point of a sustained celebration of a lifestyle that is intimately linked with an ostentatious pursuit of outdoor recreational activity. This open display is central to the democratic appeal of Pegasus Town’s idealised community whose privileging of leisure is the central, validating component of their domestic goodwill. In order to make this plain, Pegasus Lake is deliberately anchored by a ‘dedicated yacht club’, where adjoining facilities enable a set-piece cafe lifestyle that promotes and condones a watchful communitarian ethic. According to the Pegasus Town promotional brochure, Live Where You Play, these ‘uniquely positioned cafes, bars and restaurants’ will provide the focal point for a community whose leisure centre can offer rental facilities for everything from ‘surfboards and kayaks, to bicycles and sports equipment’. The promotional emphasis of these recreational options is heavily accentuated to not only suggest a limitless possibility in the pursuit of leisure options, but also to emphasise the benevolent centralisation of these pursuits within a watchful community of like-minded citizens. This centralisation brings to light the role Pegasus Lake plays in the incorporation of the adjacent leisure zones as mainstays of the sedate, family friendly conditionality of Pegasus Town itself. Best expressed by the lake’s swimming bay, who’s temperature-controlled-lifeguard-supervised-shallow-water-sanctuary, exist as the prototype of domestic contentment,15 Pegasus Lake is a convenient centre-piece for Pegasus Town’s conditional appeal. Operating at the level of corporate enclosure, Pegasus Town’s promotion deliberately uses leisure as a productive rite of citizen affirmation. Thus, the self-regulating, affirmative-value saturations that proliferate throughout Pegasus Town’s accommodation of leisure as a regulated and durational experience are symptomatic of the benevolent incorporation Pegasus Town’s idealism promotes. As such the outlying surf- club and equestrian centre meld seamlessly with the wholesome kid-zones whose wave pools and skate parks are similarly those deliberate concentrations which serve to universalise individual experiences as a durational embodiment of Pegasus Town’s leisure ethic. Likewise the four kilometres of Pegasus Lake’s shoreline joins with the two hundred and fifty acres of reclaimed ecological wetland reserves that surround Pegasus Town to create the benevolent broad-walk of self retreat nature solipsism in which even the more demur individual can still remain responsive to the communitarian ethic of recreational display.

Pegasus Town’s economy of leisure is underwritten by the durational appeasal of an experience that is designed to enact self-serving rites of corporate benevolence. This form of enclosed social interaction is central to the open space planning of Pegasus Town. This regulation, while masquerading as the open and free zone of permissibility is vital to the deliberate promotion of a shared communitarian spirit that reinforces Pegasus Town’s own incorporated values. For instance, the strict requirements to blur the ‘graduation of boundaries between homes and public spaces’16 is indicative of the level at which the transferral of public space has been conditioned by the privatisation of all forms of social space. The public-rites of recognition which such planning calls forth are entirely connected to the conditional levelling that Pegasus Town’s corporate vision is pursuing on such a large scale. This incorporation is the core proponent of Pegasus Town’s self-enforced seclusion as a satellite enclosure that allows ‘local people to live where they play’.17 This seclusion is deliberately enhanced by Pegasus Town’s insurmountable positioning between beach and eco-wetland reservations. This entrenchment is central to the town’s entranceway which arches through the three acres of Mapleham’s golf course as both buffer and barrier. As the developers explain in their Mapleham Pattern Book, Pegasus Town will not be ‘a disconnected vision of city suburbia, but a gentle transition that embraces the rural landscape and imparts a quiet order and underlying sense of harmony with the surrounding environment’.18 Such enticement, both in its exceptionalism and its subtle gradation, its ‘gentle transition’ from working mire to quiet familial life, happily situates Pegasus Town as the quintessential site of a self-serving aggrandizement. Only too ready to universalise the Kiwi condition in order to exclude and circumvent, Pegasus Town willingly placates its idealised citizen as the incorporated body commensurate to its needs. Pitched to anyone with market entrance money, Pegasus Town will be that self-serving compound anaesthetically perfected by its ability to provide the ‘ready access to the ideal mix of quality amenities and opportunities for work, recreation, education and lifestyle’.19 In this, lifestyle is a durational embodiment of opportunity, work, leisure, and education whose predetermined, promotional enclosure, ensnares Pegasus Town’s idealised citizen as a quintessential family-first utopia.

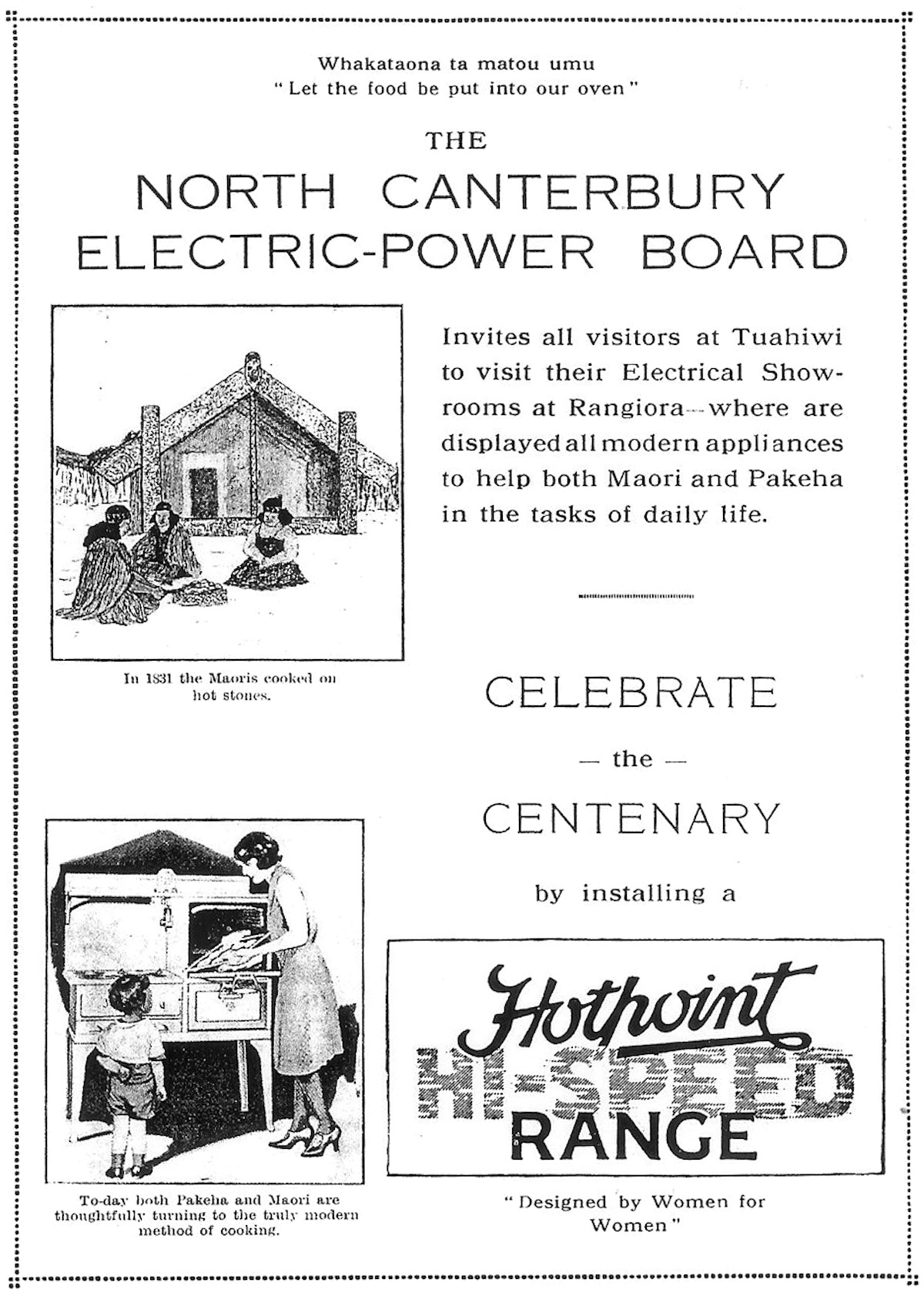

It should come as no surprise that Pegasus Town is conveniently placed to take advantage of a peculiar succession prone to New Zealand’s colonial origins. Situated adjacently to the old Ngai Tahu pa, Kaiapohia, Pegasus Town is perfectly placed to inherit the mantel of modernity’s succession that the historiography of Kaiapohia has always so neatly encased, celebrated and ensured. In fact the major source and impetuous of this history, the totemic statue, erected on site in 1899 at the behest of Christchurch’s impending jubilee celebrations, suitably turns its back on the Pegasus Town’s arch leisure domain, the Mapleham golf course in both a moment of deferment and benign parody. Erected to mark the site of a thriving pa that benefited from its fortuitous position as a middle ground for the inter-island greenstone trade, this historicisation deliberately celebrated an era in which European mystification could locate the indigene’s prime zone of romanticism. Prim and proper in genre ready dress, Kaiapohia easily served the native good looks of a pre-industrial village lifestyle with benevolent back to nature Arcadian tropes drooping with appeasal detail for Euro-benefaction. More important to this historicisation though is the neat encapsulation ensured by the interruptive agency of the Ngati Toa, under Te Rauparaha who embodied the grotesque edge of a remonstrative Maori in need of the decency and salvation of Euro-Christian conquest. Te Rauparaha’s conquest and subsequent razing of the pa is amplified by European historiography as the indecent, cannibalistic moment of conquest as an excessive and sullied edge of the native-indigene trapped within the base-instincts of Arcadia’s solipsistic romanticism.20 Such projection works neatly alongside the proprietorial conquest of New Zealand with its utopian pastoral moxie that appropriates the Arcadian rite of natural settlement and updates such harmony into the better living mantra of furtive civilisation rhetoric. Even during the 1940 centennial exhibitions the Kaiapohia monument is still being used as a rallying point in which New Zealand is the benevolent conquest, sparing electric ovens and domestic housing to a once sprawling, Neolithic culture too prey to the temptation of an unrestrained nature with its gluttony, sloth and barbarism clamour to fend for itself.21 In 1990, when the state and statue underwent bicultural re-evaluation, the Arcadian rite of passage was birthed newly in the evocative mapping of the pa site onto the potent, mythopoeic image of the whale whose pre-historic span to persecuted icon of capitalism’s industrial reach makes plain the old-world charm of Maori life within its pre- European idealism.22

Conflating a history of proprietorial aggression and pioneer determination with the self assured reclamation of wetland preservation, Pegasus Town endows their citizens with a self-affirming experience of environmental enclosure. Central to this is the preservation of an explicit line of continuity between Pegasus Town and the idealistic charm of the older Ngai Tahu world. Orientated so that the ‘main-street of the new town is aligned to form a visual and physical direct line of contact between Kaiapoi Pa and the Tutaepatu Lagoon in the south east’,23 the planning of Pegasus Town has gone to great lengths to sustain this adjacent co-relationship. Perhaps the most insidious component of this continuity emerges in the conservation values surrounding the re-establishment of the ‘coastal lagoon known as Taerutu’. ‘Substantially drained due to farming activity over the last 175 years’, this perseveration is being carried out under consultation with Ngai Tahu, and seeks to return the costal habitat to its pre-European condition. Co-joined to Pegasus Town’s own development as idealised site of modernity, Infinity Investment Group emphasises that the irrigation systems for the Mapleham golf course and surrounding parklands will be returned to ‘the Taranaki Stream or the wetlands in better quality than existing stream water flowing in that same stream currently’. Likewise, Infinity Invest Group’s adoption of mahinga kai as a conservation value seems to be directly connected to Ngai Tahu’s avid concern for the vital health of the restored ecosystem’s fauna. Special mention is made of the re-establishment of ‘tuna (eels)’ in sufficient quantities as though to reinforce the explicit division between acceptable provisions within acculturated tastes. This contrast becomes more explicit when back dropped against the development of an old mill centre in Pegasus Town itself, which will showcase the produce and crafts of the regions agricultural bounty by paying specific attention to the burgeoning wine and cheese industries. Such segregation creates a specific division between Anglo-middle class taste and the down-at-heels charm of old-world Maori still delighting in the rustic, hunter-gatherer fare of native wood pigeons, eels and mud-fish. Even if such contradictions slide inadvertently past the Pegasus Town citizen, the wetland area’s purposefully specific, ‘interpretation centre’ ought to make this co-relationship plain. The added value of this duality carries the ideological benefit in which the age-old process of colonial usurpation has always been paved by proprietorial acts of improvement that conveniently reinforce a self-validating conceit purposefully specific to privatised ownership.

Entirely conflated and contained, Pegasus Town is pitched perfectly for the universalised consumer who is hidden behind what Margaret Crawford has called the mask of diversity which has always ensured a ‘fundamental homogeneity’.24 Under such a reign of intoxicating safety and re-assurance, this corporate glove produces an aesthetic experience, which Rem Koolhaas has linked to the enticement of civic servitude. Claiming that public life has been replaced by Public Space™, Koolhaas has shown how the urban has been reduced to the urbane by the removal of the unpredictable through an overdose of imposed civility by concentrating the lived experience and interaction of city’ inhabitants into zones of permissibility.25 Similar strategies are currently being deployed in an outlying Canterbury Library for the new sub-division estate of Parklands. Spatially restricted this library regulates through permissive allowance deploying rhetorical ‘flexi zones’ to create a portable and collapsible library regimented by time allowances.26 When adapted back to Pegasus Town’s permissive sanctuary of an amalgamated communal responsibility with traditional conservatism universalised, such allowances create the blank slate in which pastiche emotion emerges. This is neatly encapsulated by Koolhaas in this defamatory moment:

The secret of corporate aesthetics was the power of elimination, the celebration of the efficient, the eradication of excess: abstraction as camouflage, the search for a Corporate Sublime. On popular demand, organised beauty has become warm, humanist, inclusivist, arbitrary, poetic and unthreatening … Colour has disappeared to dampen the resulting cacophony, is used only as cue: relax, enjoy, be well; we’re united in sedation … Why can’t we tolerate stronger sensations? Dissonance? Awkwardness? Genius? Anarchy? (169)

It is all too easy to understand the impulse behind Koolhaas’s derision. Pushed to the extreme, modelled on such exceptionalism and heightened by its fervent aspirational content as a marketing moment, Pegasus Town is entirely that corporate ideal fully enmeshed within its regime of aesthetic appeal. Given time though, this edge will lose its heightened qualifiers as they proliferate through subsequent diffusions as like-minded developers seek to gain access to this added-value property market. I think this impulse alone makes it important to understand both the ambiguity and discomfort of Pegasus Town as a new enterprise. Its self-retreating edge as a secular and corporate enclosure is entirely indicative of New Zealand’s continuity as a colonial enterprise. While Pegasus Town may be mired by its overloaded content, it still makes sense to see it as an entirely appropriate point in which to face up to the constant negotiation of New Zealand’s validation. New Zealand has always been an idea whose predominate address has been one of proprietorial responsibility and selective communitarian ethics. Pegasus Town’s emergence must be seen as part of the constant evolvement of New Zealand’s ongoing class segregation through self-avowed retreat. One of the obvious ways of seeing this is to compare Pegasus Town’s self-enforced segregation through entreaties of privatisation with simultaneous developments in which a self serving multicultural street-literate massive is being promoted by benevolent corporate companies like Huffer whose re-creation has similar seclusions in mind.27 In setting up Pegasus Town as the all too obvious example of the limitations of such privatised blessings, we often miss how unwittingly we admit ourselves to similar seclusions on an almost daily level.

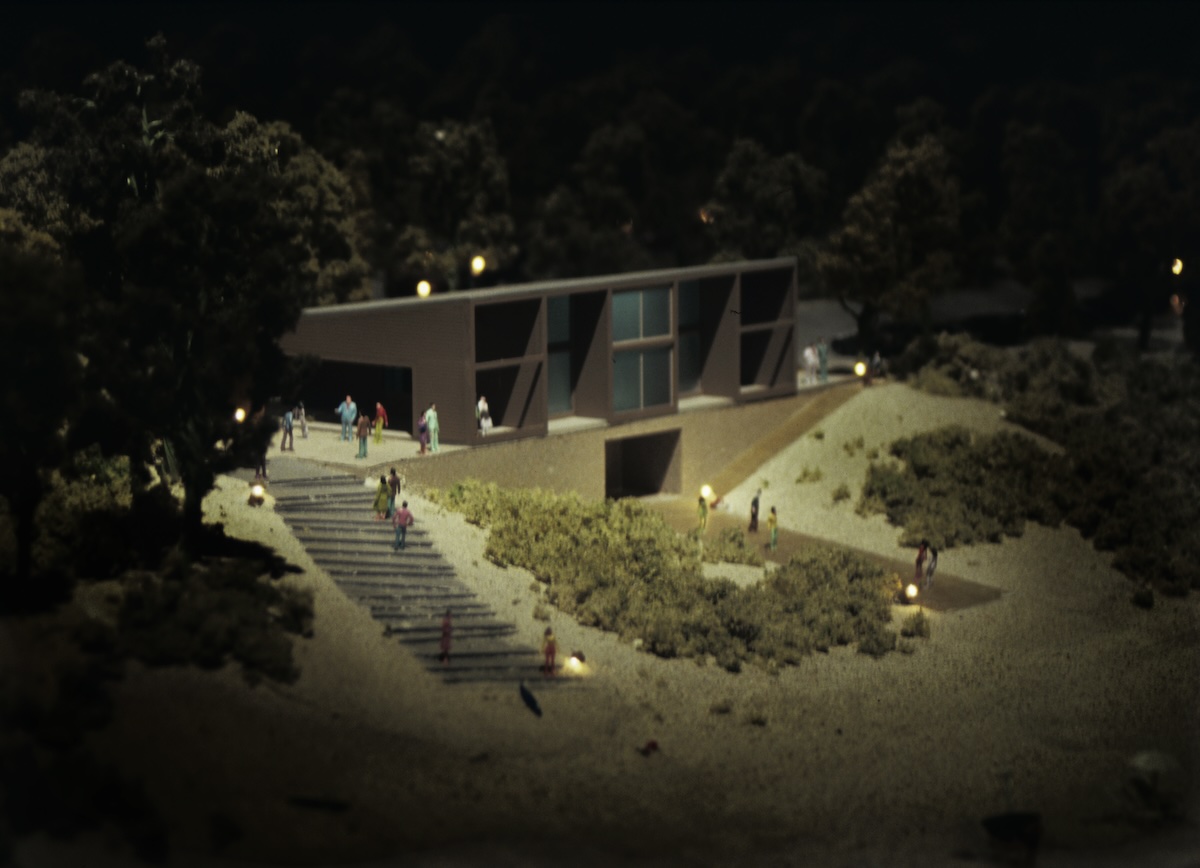

At the moment Pegasus Town largely exists as a promotional desire. Nothing exemplifies this more than the sale day, which was held at Pegasus Town’s promotional headquarters in Addington. There, surrounded by Australasia’s largest scale model, which lays out the Pegasus lifestyle in 1:100 scale, Infinity Investment Group’s idealised clients compete to purchase individual lot units. With sales exceeding one hundred million dollars, the sale day itself becomes shorthand for the aspirational ease of Pegasus Town’s easy-living lifestyle. Such hype is the natural accompaniment to Pegasus Town’s promotional con- glomeration which takes so easily whatever it wants and glosses all to performance sheen. Swirling around the Pegasus Town model is an omnipresent grouping of promotional enticement. Played out on a range of overhead video monitors, interactive touch-screen DVDs, banners, murals and life size tableaux, these adjacent scripts highlight the exceptional range of Pegasus Town’s easy-living, life-style pursuits. Whether it is kayaking, surfing or alfresco dinning, Pegasus Town’s enticing leisure options are presented as a dizzying array of opportunity, all within easy reach and often two if not three or four, at a time. Over- saturated by this promotional frenzy the insatiable consumer is lured into a dazzled and disorientated state perfectly receptive to the benevolent approach of the Pegasus Town consultant. At the very least, this over-saturation leaves the dazed consumer enthralled before the sheer scale of Pegasus Town’s utopian aspiration. Similarly ominous is the model’s enactment of day and night lighting which figuratively embodies the very enclosure of Pegasus Town’s lived duration. This dramatic lighting entices the future citizen to play out a fictional encampment, from day to night, as self-enclosed, new world fantasists. Encouraging such narcissistic indulgences, the Pegasus Town dream, glossed by its marketing perfection, its speculation carried to excess, is a fully immersive fiction wilfully surpassing reality. Pegasus Town’s greatest marketing asset is this speculative encouragement which lures consumers by eagerly abetting their desire to abandon the contemporary limit in hope of future perfection.

Couched within the frenetic maintenance of Pegasus Town’s future benevolence is an insidious potential to eclipse the contemporary moment. Indicative of its utopian aspiration, Pegasus Town sustains itself through a cursive present that over-saturates its promotional appeal. Through its permissive regulation of not only the idealised citizen, but also the idealised lifestyle, Pegasus Town offers an aggressive retrenchment which seeks to abandon contemporary society through its plaintive appeal to an idealised future. Through its aggressive eagerness to accommodate traditional family values, Pegasus Town overdoses on planned civility through contingent appeals of accommodation. Heroically envisioned, Pegasus Town’s scale conflates the individual with the communal. Seduced by its incorporated regime of participation Pegasus Town’s restrictions appear both malnourished and over-engaged. Its rational planning, its cordoned lifestyles, accommodate a proliferating speculation only by reducing hedonistic pleasure safely within a moralistic code of familial ethics. Over saturated in its marketing moment, Pegasus Town’s vision is grandiose and singular. Its core promotional ingredient is its direct appeal to the adept consumer, self-actualised and fully capable of living out Pegasus Town’s contradictory induction of domestic contentment as the idealised lifestyle. With its fantasy of ostentatious domestic bliss overtly displayed, Pegasus Town is a speculative encampment which seeks to step outside of history in order to re-create a foundational fiction all of its own.

The uncanny flipside to Pegasus Town’s marketing is the Pegasus Town site itself. This construction site, barely at stage one in its completion plan, is an empty, desolate plain. Recently deforested, heaped piles of logs and waste debris fulfil a totemic function across its barren terrain. Creating a maze like structure, these piles create a focal point for an otherwise daunting weave of access pathways that wind through this cleared landscape that awaits future perfection. As though underscored by a surreal validation, wrecked cars and abandoned squatter sheds are left in tact on the fringes of these pathways. Tagged with neo-Nazi signs, marijuana leafs, and ‘welcome to hippy land’ slogans, these wrested objects grapple with the underlying future of Pegasus Town’s dream. In the service of Pegasus Town’s marketing these relics from a degenerate era are the obscene embodiments of a culture the traditional family is seeking refuge from. Hidden from view, enclosed in the sedate, saturated borders of the corporate enclave Pegasus Town embeds even these degenerate fictions within its own make-over plan. This regeneration, this growth strategy is the finalising moment of Pegasus Town’s declarative community. It wishes not only to allow ‘people to live where they play’ but also to eclipse history itself. Their retreat is a utopia speculation, an aspirational motivation that exists most acutely now in its fictionalised, marketing moment. Like the billboards for a property development in Christchurch’s suburb of Harewood that claim, ‘Cul De Sac – it’s French for “peace & quiet”’ — Pegasus Town re-invents the domestic mould through its own rejuvenating idealism. The levelling that this promotional re-investment requires contradicts every contemporary reservation, which has seen cul-de-sacs become a by-word for suburban anxiety and cultural malnourishment. But then, reservations aren’t the domain of the fractured and disembodied communities whose life-styles are so saturated by emulation and aspirational becoming that make up the fictively adept client-base of Pegasus Town’s over-polished, marketing moment. One look at the cover of the Pegasus Town brochure, in which a white, middleclass, couple gaze longing-ly out to sea, hands held, in a furtive yet distracted anticipation of the future they deserve, ought to have made this plain.

Footnotes

This is from Infinity Investment Group’s main promotional brochure, Live Where You Play, which condenses the Pegasus Town vision into 36 full-colour pages. Deploying a kind of amalgamated vision, Live Where You Play uses a combination of sketches, photos, snap-phrases, bullet point explanations and sound bite quotes to create an aspirational textualisation of Pegasus Town. It is un-paginated but most quotes are pulled from obvious, easy to find sections. For instance this quote comes from the very first sentence of the brochures introduction spiel. ↵

Live Where You Play. Pegasus Town promotional brochure. ↵

Mathew Hyland, 'The Teeth of the Underdog’s Saw', Natural Selection (Issue 4: 2005: 5.7). ↵

The obvious place for this investment is the Live Where You Play brochure. In the introductory page, it is stated that "Pegasus has been conceived for the traditional Kiwi Family". Further on in the brochure, under the heading, ‘homes to suit you lifestyle’ Infinity Investment Group claim that "Pegasus is built around the traditional Kiwi Family". This traditionalisation also occurs in more public arenas as well. For instance, Bob Robertson’s, Infinity Investment Group’s chief executive, makes a privileging claim for this idealised citizen in an interview with Steve Braunias for the Sunday Star-Times. Claiming that "my vision of Pegasus is based on the perception of what I would want" Robertson makes explicit the underlying preference that is contrary to their oft stated non-elitist version of "the traditional Kiwi family". See, Braunias, 'A Town is Born' Sunday Star-Times (April 23, 2006: C2). ↵

This claim to the North Canterbury vernacular is made in the The Mapleham Pattern Book. Pattern books are an essential for a development of this scale. As Andrew Ross has pointed out, pattern books are both a guarantee of future quality, long after the developer has left, and "a formidable marketing tool, lavishly illustrating the ambience of classical, civilised living for those in the market for good taste". Ross also points out that pattern books, long the domain of the architect/planner, have since the 1920s become more the product of the lawyer-property developer. See, Andrew Ross. 1999. The Celebration Chronicles. New York: Ballantine Books. (87–88). Pegasus Town is represented by two pattern books. The Pegasus Pattern Book covers the multi- zoned domestic and retail areas, while The Mapleham Pattern Book covers the sections overlooking Pegasus Town’s golf course. The Mapleham sections are significantly more expensive and perhaps more aspirational in tone. Situated at the entranceway of Pegasus Town’s satellite enclave these properties are the very embodiment of Pegasus Town’s communitarian ethic, which is both open and yet securely privatised. ↵

The Mapleham Pattern Book, 3. ↵

The Pegasus Pattern Book, 2. ↵

The Pegasus Pattern Book, 2. ↵

‘Mainstream’ sloganeering was deployed excessively by the National Party during the 2005 New Zealand election. When pressed to define mainstream identity, the National Party’s leader, Don Brash, was always vague and non-committal. In a general sense it was taken to mean anyone that supported National and was used as a crude divisive measure which allowed the National party to portray their counterpart, Labour as a left leaning, out-of-touch, elitist, party leading New Zealand down the garden path of wilful obscurity. ↵

See, Braunias, “A Town is Born”, Sunday Star-Times (23 April, 2006: C2). ↵

Andrew Ross has shown how Celebration’s promotional marketing played "to people’s loathing for strip-mall landscape, its gaudy commercialism and plug-in housing tracts". Billboards promoting Celebration showed two girls at play on a swing set with the slogan, "isn’t this reason enough for Celebration". These were placed along "arteries that steer motorists past concrete and neon thickets of fast-food shacks and discount malls" to exacerbate the idea that "Celebration would be yet another fresh start in a world gone wrong" (3–5). Pegasus Town’s promotion is similarly conceived. Placed alongside commuter routes or on inner city busses, Pegasus Town adverts promised domestic contentment unhindered by the rush of urban daily life. Similar conceits were played up in billboards that showed happy kayakers taking in the serene eco-wetland reserves which unlike in Christchurch were right at the doorstep of every citizen. ↵

This is from the break out quote from Bob Robertson on the second page of the Live Where You Play brochure. ↵

Robert Bruegmann (2005). Sprawl: A Compact History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (109). ↵

Pavletich in Matt Philp, 'Backing the ’Burbs'. The Press. 16 September, 2006 (D3). ↵

The Pegasus Town promotional brochure, Live Where You Play, describes Pegasus Lake as "an unrivalled aquatic playground" which will provide "sheltered, private beaches, family picnic amenities". A "temperature controlled and filtered bay" will provide a "golden sand beach" where "safe, shallow water with lifeguard supervision" will create "an ideal environment for family fun". ↵

The Mapleham Pattern Book, 4. ↵

In Live Where You Play, Bob Robertson is quoted as saying, "we are building [a] community around a lifestyle, one that offers all the benefits of one of the best locations in the South Island, to allow local people to live where they play." ↵

The Mapleham Pattern Book, 2. ↵

Entrance into Pegasus Town does not come cheaply. Small sections within Pegasus Town are priced around the $150,000 and $190,000 mark, while sections in the more prestigious Malpeham zones are priced between $300,000 to $500,000. If Pegasus Town follows New Urbanist developments in America these prices will escalate once Pegasus Town is fully up and running. Anthony Flint has noted that houses in Seaside, Florida one of the first New Urbanist developments today sell upward of $1 million. Andres Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk and Jeff Speck the architects of Seaside gleefully note these houses now sell for "twice the price of a twice as large oceanfront lot in a nearby subdivision". Similar patterns occurred at Kentland’s where houses sell for a $30,000 to $40,000 premium over comparable properties. See, Flint (2006). This Land. Baltimore: John Hopkins Press (64). Duany, Plater-Zyberk, and Speck (2000). Suburban Nation. New York: North Point Press (106-7). ↵

One of the central figures in the foundational historicisation of Te Rauparaha’s sacking of Kaiapohia Pa was Canon James West Stack. In his commemorative history, Kaiapohia, The Story of a Siege, Stack deliberately uses Te Rauparaha’s sacking as a convenient grotesque that validates New Zealand as a domesticating impulse. A similar use of Te Rauparaha’s sacking as "a scene of unparalleled horror and savagery" to inflame a European sense of propriety and decency was invoked by a successful tour book of the 1890s. See, Stack (1893). Kaiapohia, The Story of a Siege. Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs, and the Union Steam Ship Company of New Zealand (1884). Maoriland, An Illustrated Handbook to New Zealand. Australia: George Robertson and Co. (109–110). ↵

There is an ad for electric ovens in the Kaiapohia Pa Centenary: Programme of Celebrations (1931). Christchurch: Kiwi Publishers, (2000) which specifically draws upon this benevolent usurpation. ↵

See The Press. 21st January, 1989 (21) which documents the 1990 revamp of the site. ↵

This and other quotes included in this paragraph come from the Infinity Investment Group’s ‘Pegasus Town Information Sheet’, which is included in the Pegasus Town promotional package. ↵

Margaret Crawford, 'The World in a Shopping Mall', Variations on a Theme Park, The New American City and the End of Public Space. Ed. Michael Sorkin (Hill and Wang, New York, 1996: 3–30). ↵

Rem Koolhaas (2004). 'Junkspace', Content (162–171, 169). ↵

The library’s website promises "that a visit to Parklands Library will be unlike any other, with unique time zones appealing to different customers at different times of the day". See, www.library.christchurch.org.nz/parklands. Thanks to Kate Montgomery for drawing my attention to this. ↵

I don’t think Huffer is the obvious choice for this example. Coca Cola’s 2004 enlistment of Nesian Mystic to promote "summer the way it should be" is probably more overt, but in using the obscured version of Huffer, I merely want to draw attention to how insidious this culture of aspirational marketing has become. For a more drawn out version of this, see my article, “Happy- go-lucky-land-of-pleasure”, Ramp (Winter, 2005). ↵