Archæology of Frail Re-territorialisation: Dane Mitchell’s Barricades – David Craig

Social engagement is back on numerous arts agendas. This is welcome, especially in the aftermath of smart and cynical PoMo, and the kinds of apotheotic deconstruction that distracted progressive activism in the 80s and 90s, even as neoliberalism went into full warp drive. Better yet, not all of the new art of social engagement is bent on imposing naïve utopian, gallery based, hard radical, or microsocial relational/communitarian counter narratives. This is good, and rather more realistic, in a time when what’s really happening is that systemic neoliberal arrangements are bedding in and institutionalising.

The smarter art starts, rather, from registering a certain kind of cool acceptance of the situation, and too of the fact that most art practice and institutions are a long way from current political frontlines. It is even prepared to acknowledge and play with the kinds of impotent rage in a social or territorial teacup which is so often the lot of radical social actors these days.

With these knowing constraints, it seems, art in practice can still enact a number of socially engaged moments, pointing as it does to both the necessary attitudes and too to some of the means of current political practice. By means, I mean things you really need to be a real political activist (artist) these days. Things like:

- Practical interim territorialising modalities (such as barricades)

- Discernment of both immediacy and big picture distance

- Close realist/historical/archival study

- Complex relational analysis

- Knowing how to make use of bits of institutions not set up for activism

- Clear, hard use of images and signals

- Hard nosed deployment of form and craft

All of this, economically, nicely weighted, was on extensive display in Dane Mitchell’s Barricades show at Starkwhite, Auckland, Nov–Dec 2007. Though by synchronous virtue it resonated strongly with the territorial/ terror/roadblock politics emerging in Tuhoe country, the show wasn’t overtly political in any particular directional sense. But it did lay out very clearly indeed the kinds of positional problematics artists engaging socially and politically must these days work out of. Laid them out, that is, in what was both a kind of well appointed display, but also a kind of post archæological dig arrangement of devices, documentation, analytic schemas, and more. The mark of its success was how far it went beyond rage in an æsthetic/formal/institutional teacup, and how close it came to referencing the sharded and contingent realities of revolution and micro-re-territorialisation in so much of historical geopolitics.

De/re-territorialisation, barricades and marginality

Civilized modern societies are defined by processes of decoding and deterritorialisation. But what they deterritorialise with one hand, they re-territorialise with the other. These neoterritorialities are often residual, artificial, archaic: but they are archaisms having a perfectly current function, our modern way of imbricating, of sectioning off, of reintroducing code fragments, resuscitating old codes, inventing pseudo-codes and jargons.

Deleuze and Guatarri, from The AntiOedipus [257].

Barricades are like borders, in that they instantiate territories, often quickly, temporarily but, as this show makes clear, repeatedly enough to warrant consideration against a range of parameters: political, social, and cultural. In this, they operate within patterns of de- and re-territoriali- sation, wherein the dominant actors have much greater territorialising powers—both de- and re- than the marginal.

Capital’s agents want it to flow, globally, beyond boundaries, to enable full realisation of its values. De-territorialisation thus has powerful allies: removing tariff or capital account barriers, opening countries and commu- nities up to foreign ownership and easy repatriation of profits has been achieved with increasing ferocity by neoliberals now, as it was by older, more classical liberal imperialists in previous free trading eras. Territories strong and marginal alike might want to protect their markets, their crafts, their primary produce from such openings, and they might succeed in this for a time, in a “movement of re-territorialisation that goes from the centre to the periphery [which] is accompanied by a peripheral re-territorial- istion, a kind of economic and political self re-centering of the periphery, either in the modernistic forms of state socialism or capitalism, or in the archaic form of local despots” [Deleuze and Guatarri, 258]. Either way, they will need some kind of barricade.

Marginality, being precarious to other people’s territory, has more generally always called for barricades of one kind or another, in order to secure, somehow and for however long, what territory was encroachable. In fact, even more generally it could be argued that marginal people depend to a much greater extent than others on things being territorially available to them: things like security (finding somewhere safe to sleep and work), economic opportunity (the ability of an informal sector such as a street hawker on a street corner or an itinerant route, having a job within transport reach), access and movement in and around locales of economic opportunity (migration, the ability to find refuge/refugee status across a border, freedom from police or property owners harassment for gathering of firewood or subsistence ‘poaching’ of common property resources, such as fish or firewood from degraded forests). In all these things, they need protection, they need residual historical and customary access rights to be recoded, allocated and defended; they need public advocacy and a real safety net to be constructed, artificially if necessary; and they need rights not to be detained, arrested, plundered by boundary interdiction agencies, deploying and counter-deploying whatever jargons and pseudo-codes will do the trick.

In this, as Deleuze and Guatarri had it, the marginal, bricolage oriented re- territorialisation moves and works with whatever is at hand—a limited set of rules, and a finite and heterogeneous set of tools: rights (however sketchy and tenuous), relationships (ditto), physical means (again, ditto). Here, they create a contingent but nonetheless common évental rupture [Badiou’s term] necessary because of (and structurally enabled by) the less-than-total position of the state in any given situation. All these rights and protections are thus little barricades, partial and contingent re- territorialisations, which may be framed in universal rights or even institutional terms, but which may nonetheless seem frail and of little consequence.

But again, for those on the margins, they are means of basic survival. In Cambodia, for example, the poorest rely on access to common property resources (river fisheries, forest flora and fauna, water and common land, access to public areas around markets for hawking produce) for a signifi- cant part of a subsistence livelihood [See Ballarad et al., Fitzgerald and So]. As these resources come under population and capitalist expansionary/ enclosure pressure, the squeeze is felt first and hardest by the poorest; and it is they who need protection. They get it, as with barricades, by appropriating it from the powerful: seeking a patrons’ protection, invading public and undefended private land, tearing things up and taking them home to bolster basic household economy.

This reliance of the poor on barricades is more than a little ironic, because it is territorial boundaries that have in general been used to control and police the marginal: to contain and constrain their move- ments, their mass/mob movements. And, of course, to protect property and lifestyles: by maintaining tariff barriers against agricultural produce from the poorest countries; by maintaining strict migration and border security regimes; by invading countries which can be seen as harbouring threats; by enshrining private property rights at the core of law, and having the state itself defend them against petty criminals. And, ultimate- ly, by ghettoising the poor, keeping them where they are, constraining them, locking more of them up in jails, forcing them into low paid work or regimens of close disciplinary supervision by their Work and Income case workers. Territory, like property and capital, is in other words primarily the domain of the non-marginal, and they use it to control. This means re- territorialisations in the interests of the poor are frankly rare, often temporary, usually enabled by short-lived outbreaks of violence, and seldom sustained for long against better organised class interests.“For a while, though”, as Deleuze and Negri put it, “they have a real rebellious spontaneity”, wherein “what counts in such processes is the extent to which, as they take shape, they elude both established forms of knowl- edge and the dominant forms of power”.

Commonly, power can and does have it both ways against the marginal. When it needs to it can literally cut a swathe through their territory, as happened in Haussman’s Paris and in the rookeries of inner London. Grand avenues, with streetscapes the length of cannon shot scope, such as those Haussman gave Paris, made barricading and the illusive use of local knowledge of dense territory just that much harder [Berman 1983]. The rich, then, de-territorialise and re-territorialise with much greater freedom: and the long term outcome of this churn creates the realities of class, difference, marginality and stigma we see mapped across cities, north and south relations, ethnic and regional differences, and on either side of politically and economically significant borders.

Borders, old and new, then, are the barricades of the rich and power- ful, and so they shift much less commonly, and are ideologised, through narratives of nation and land, blood and soil, in much more powerful ways, which the poor, usually to their detriment, can only imitate, and then enforce in turn against those yet more weak and vulnerable. For those bounded out, or in, as in Gaza, the natural remedy is the shortest termed of all: you blow a hole in the wall, or launch a bomb over it.

Micro-territories via barricades: practical realities and distances

All this and more is dug up, it seems to me, by the close and archæological technique of Dane Mitchell’s show: exhuming, documenting, poring over, sketching possible relationalities, re-assembling. These kinds of activities are something Dane has been up to for a while now [see Garrett], Barricades pulls the elements together most powerfully yet. Its archæology, joined to and realised in a kind of mock museum display æsthetic, works both on its own archæological terms, and also within a wider, more immediately referenced sense of barricading and territory, wherein which the museum itself has had the shit kicked out of it, through the simple appropriation of its walls to reference another, even, more immediate barricading exercise of our own recent national experience.

The contingent, desperate re-territorialising work of the marginal is in itself an important topic for any art in any time and place. There are awful risks involved for artists venturing there however, in that their own class position usually means they bring a set of middle class curiosities and detached, touristic dispositions to the task. They may even arrive with social work intent, or naïve political agendas.

An obverse move, however, is to appropriate marginal barricade struggles as a metaphor for other kinds of marginalities, including æsthetic ones. Here, the trick is not to make art, for all its inbuilt and inward looking constraints, the beginning and end of the story, with the barricades again just a piece of voyeuristic travel. The thing is, art really does find itself in a range of marginal situations and structural violences which are significant and important.

The other thing is that there is a very legit and necessary role for art that has something to say about territoriality, and how it works in relation to people and places, both inside and outside of cultural practice. Strug- gles—social, political, economic, cultural—will always take up symbols and be impelled by representations, and here artists will find themselves both drawn into the vortex by the compulsions of the causes, and also by their protagonists. The collusion and conjunction is a natural one, but not, given the various distances between the actors, an easy one. Better then to somehow get some of these distances right upfront, out there: distances of class, of social and economic organisation, structure and history, geography and struggle—formed identity.

This getting of distance upfront in a number of knowing ways is a primary achievement of Barricades. Yes, most (though by no means all) of these struggles took place far away and long ago: inevitably, then, we look back with some kind of distance, at the kinds of small black and white images Mitchell has collected in his book-bound archive. Or we look back via representations which have been heavily invested in ways we can’t even fully know: formed and reworked by someone else.

Marginal revolutions, affinities, and forms

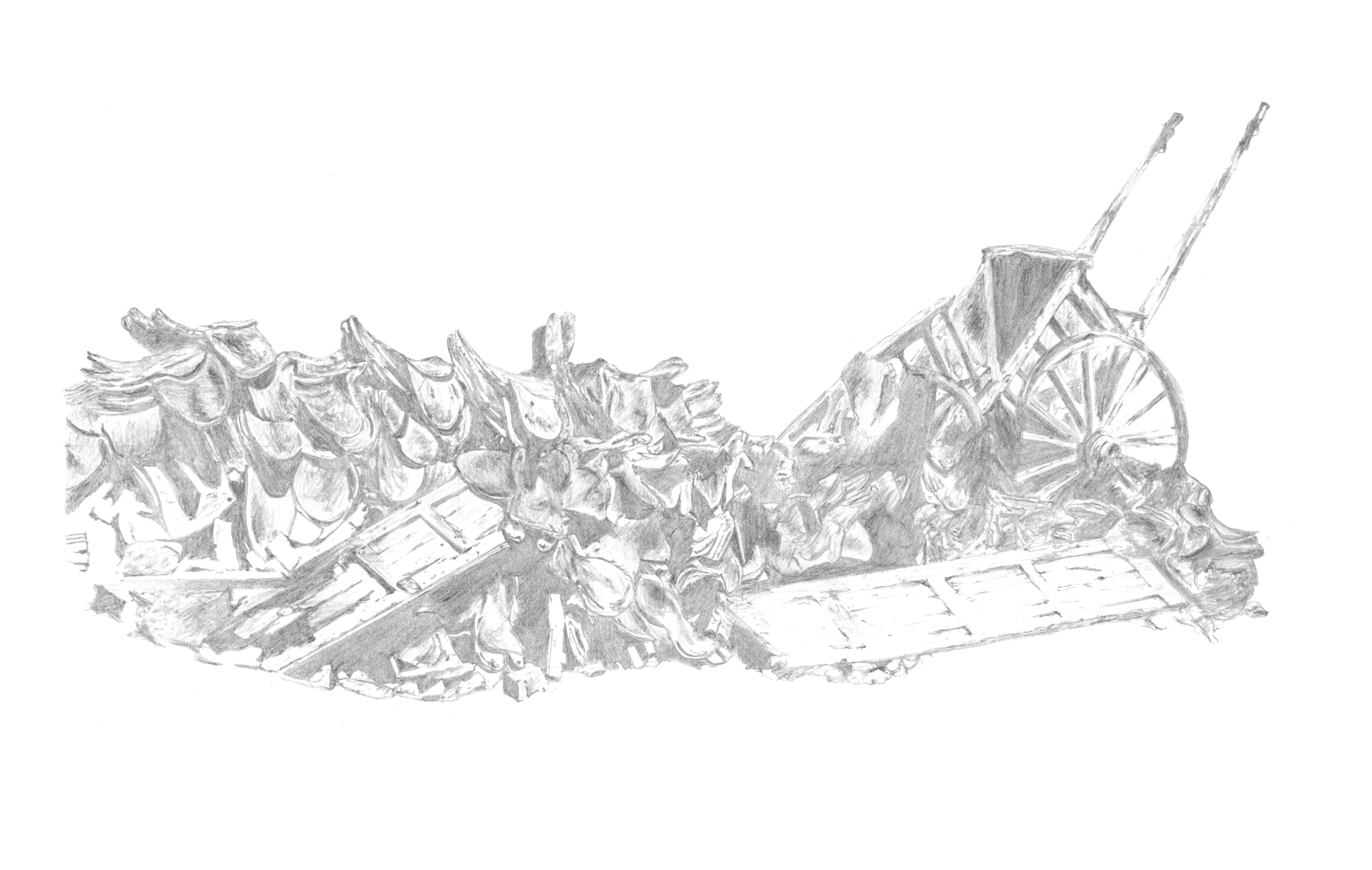

Here, the show’s clearheaded, realistic response is to metonymically and formally realise these distances by rendering the images again, and in a mode which at once gestures at and conspicuously fails at an immediate realism. The realism of the show’s colour pencil drawings, in other words, references well the powerful historical affinities between realism and politics, while rendering a more immediate engagement at the same time something frail, distant, able to be only personally and painfully retained by the artist insofar as there is a painstaking attention to detail, and respect to a somewhat distant specificity.

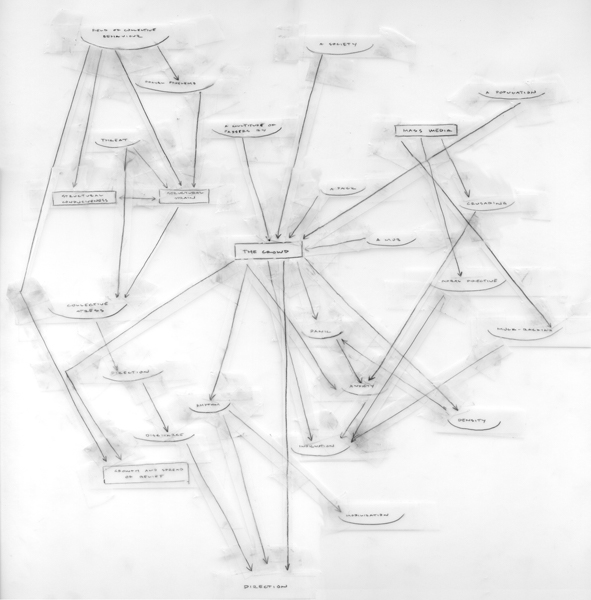

These distances, of course, in the context of Antipodeal art, have another whole set of references to marginality: marginality of art practice located some way from core institutions and territories of either political or æsthetic wealth and power, but marginality which must increasingly confront the fallout from these political-economic and æsthetic turbulenc- es, happening in its own backyard. Again, formal appropriation of either the means of social and economic production or æsthetic representation is difficult: it involves tracking back over places, history, doctrine, time, and trying to lay out links and affinities, all again from great distance, so that the links seemingly available are tentative, in need of ongoing revision, bewilderingly plural: as Mitchell shows us distinctively in the little smudged-pencil flowcharts in Barricades.

From New Zealand, questions about how the scales and forms of our struggles relate to those elsewhere are significant ones. Most of the show, form and content, has international reference, wherein, as discussed below, the affects of our distance from them are nonetheless clearly realised. Here, Europe’s class based struggles segue easily into the still grand and intense social, political and economic struggles of contemporary Latin America. As art links between NZ and Latin America have expanded in the past five or so years’ (presence in the Sao Paulo Biennal, Auckland’s 2007 triennial [Lynn]), the intense social machinations of that region have clearly resonated here, albeit that recognition has been balanced by a keen sense of difference and distance needing to be registered.

In this show, the acceptance of distance in general has a cool, formalis- ing effect, where swords of revolutionary impulses are turned into the shiny shovels and garden wheelbarrows of a clean and uncluttered gallery space. But this isn’t to say the tyrannies of distance stamp out real revolutionary force in the show. Rather, distant revolutions act as a foil for our own more immediate ones, as the show seems to gain impetus (and necessary greater scale) for a more immediate engagement with the forms and icons of struggles here (the 1981 springbok tour Red Squad shapes of the shields torn from the stark white cube wall; the Molotov cocktails, strongly resonant with current Tuhoe roadblock/territorial politics, emptied of colour and re-forged in what inevitably seems Te Papa-esque abstract reproduction).

Starkwhite, Auckland, New Zealand,

2007 Photograph by Louise Hyatt

Vive la revolution?

Thus is distance from the conflict, and from other historical and æsthetic hegemonic engagements, registered formally: accepted, acknowledged, but also turned around into something harder: a form. It’s a form which signifies in its clear, cool and abstract way a certain definite violence. Here, however, intensities of practice and hard referencing of form

only partially substitute for intensities of politics: that, in one sense, is maybe most of what they can do, for now. So, and I think helpfully, for all the formal strengths of the show, you are left, even or perhaps espe- cially at this distance, with important uncertainties about meaning and outcome, and a sharper awareness of contingency, even in the middle of a barricade situation.

This too is apposite: barricades commonly render frail, temporary re- territorialisations; and then history, class, political economy, geopolitics move on. Yesterday’s politics, yesterdays’ forms are only a very partial guide to tomorrow’s. New temporary territories and barricades need to be put up, and encroaching hegemonic class territorialisations need to be shown up, barricaded against, however contingently, and from whatever distances.

What’s achievable, and again what you need to do it, are for the most part referenced pretty well in this show. Struggle, at once barely graspable and at the same time very immediate, might then get worked up all the way from tentative, necessarily sketchy archæology into something that is rather bigger and more definitional than the sum of its parts.

Starkwhite, Auckland, New Zealand, 2007

Photograph by Louise Hyatt

Badiou, A., Being and the Event. Trans. O. Feltham. New York: Continuum, 1988/2005.

Ballarad, B., ‘We are living with worry all the time’. A participatory poverty assessment of the Tonle Sap. Edited by Brett Ballard. Phnom Penh: CDRI, 2007.

Berman, M., All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity. London: Verso. 1983.

Deleuze, G. and F. Guatarri, The Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1972.

Deleuze, G. with A. Negri, ‘Control and Becoming’. Trans. Martin Joughin. Futur Anterieur 1. Spring 1990.

Fitzgerald, I. and S. So, Moving Out of Poverty. Phnom Penh: CDRI, 2007.

Garrett, L., ‘Small White Cubes’, On Empires. http://www.starkwhite.co.nz/story1058.html?

Lynn, V., Turbulence: Catalogue of the 3rd Auckland Triennial. Auckland: Auckland Art Gallery, 2007.