Perverting the Press: Alan Loney’s paradoxical postmodern private press – Noel Waite

&

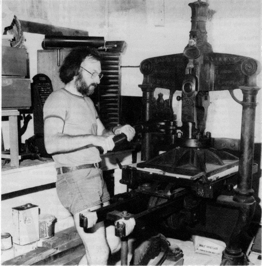

The appearance of poet, printer and publisher Alan Loney in the 1981 issue of Designscape1 is recognition of his boundary-crossing achievement. Affectionately dubbed ‘Ampersand Alan’ by legendary New Zealand graphic designer Leo Bensemann and typographical man of letters Denis Glover2 because of his frequent use of that typographic symbol, Loney is one of New Zealand’s best exponents of open form poetry, a private press printer of international repute and an uncompromising postmodernist practitioner. Although this combination at first seems paradoxical, it is the result of a persistent and intransigently conjunctive life of provocative cultural inquiry. Text and image, theory and practice, commerce and culture, art and design are all integrated to achieve what American poet Robert Creeley described as “continuing provocative wonder” [469].

In his 1990 book &, The AMPERSAND, Loney asks the question: “What of the printers, then? That is, those who... transmitted our culture with care, skill and intelligence to where we would have access to the past, whether profound, silly or boring, it doesn’t all that much matter, so long as it is access that we have.” Access has been a contentious issue for Alan Loney, having himself been excluded from certain publication outlets. In an interview with Leigh Davis, he remembers: “In the early seventies we were trying to get in Islands and Landfall and being knocked back ... We were furious. There was a set against the kind of writing we were making. Apart from the question of it being any good or not. This is the political struggle that writers have had to actually get past certain kinds of editorial prejudices.” [‘Talking...’ 58]

Loney’s response was pragmatic—to start his own press and become a transmitter of culture in addition to being a producer. The first result was the Hawk Press (1975–83), then the Black Light Press (1987–91), the Holloway Press (1994–98) at Auckland University, and the current manifestation of Electio Editions (2004–) in Melbourne (http://www. electioeditions.com/). While much has been written about Alan Loney’s poetry and writing,3 this article will focus on his engagement with book design.4 Hawk Press is the focus because its activities take place against a period of dynamic social change in New Zealand that, like other cultural movements in the 1930s and 1950s,5 was the result of cross-fertilisation in the arts. What is significant about Loney’s practice in the 1970s is its independence from nationalist agendas and the way in which it prefigures the democratisation of design encouraged by computers in the following decades. His theory-informed craft revolution had a significant impact on New Zealand’s literary and artistic cultures, bringing them closer together while at the same time providing a site for experimental practice outside traditional mainstream outlets.

The letter P

When I actually started the press I just wanted to produce better looking poetry books than the ones currently made. That went on for about three years, but the more I printed the more I got absorbed in typography and printing, and the less interested I became in publishing as such.

Alan Loney, from Designscape 12.

After a buoyant period in the 1950s and 60s, New Zealand’s indigenous printing and publishing industry had had to adapt to the arrival of television and international publishing competition as a result of local successes. High-speed, large-volume printing technologies also left little room for alternative voices, and the collaborative inertias resulting from the impact of new offset printing technologies presented a barrier to new forms of writing and design, while at the same time entrenching established conventions and practices. Consequently, the divide between commercially driven capital-intensive production and democratic consumption widened. Instead of seeking a place within this confined industry, Loney opted instead for the independent alternative of private press printing.

The private press movement began in the late 19th century in response to the decline in design standards as a result of rapid technological change. In his comprehensive book on the subject, Roderick Cave defines a private press as an unofficial press operated by the printer that prints not for profit but to produce works of some æsthetic merit for a restricted audience. While profit was not the primary motive, a number were commercially successful, such as William Morris’ Kelmscott Press. In the more common absence of profit, four other p-words characterise the output of private presses: pleasure, period pieces, perfection and perversity.

Most choose this path for the simple pleasure of printing and perhaps to produce work that pleases the hand, mind or eye; some seek only to emulate historical styles, often in rejection of contemporary trends, while others desire to print with the best materials to produce the finest books. A genuinely subversive character, to willfully resist commercial, techno- logical or cultural conventions, is possibly the rarest, but seems best to characterise Alan Loney’s motivations.

Precedent & influence

Precedents for a private press were not confined to either the 19th century or England. In New Zealand, Denis Glover shared a similar motivation with Loney in establishing the Caxton Press in 1936, although that press rapidly accommodated new printing technologies and commercial imperatives to become a small scale but hugely influential printer and publisher. Also in Christchurch, the remarkable Bob Gormack published over 120 pleasurably modest books from his Nag’s Head Press over 40 years while also working fulltime as an editor at Pegasus Press and Whitcombe & Tombs/Whitcoulls.6 However, it was from America that Loney derived the most inspiration and support, initially in the form of books but later through collaboration and distribution.

With a copy of Babette Deutsch’s Poetry Handbook: A Dictionary of Terms as his guide, he began to write poetry in Wellington at the age of 23, and, as this choice of text suggests, from the beginning there was a very strong craft basis to his poetry. Loney himself is more explicit: “The minute any writer puts one word after another, you’re involved in matters about craft” [personal]. His grounding in traditional stanza forms led to an appreciation of the importance of the breath and stresses placed on words, perhaps made more keen by his background as a jazz musician.7 Poetically, his major turning point was the discovery in 1971 in Dunedin of Charles Olson’s8 The Maximus Poems. These he considered a major breakthrough, on account of Olson’s ability to include a wide range of materials in a single poem, and how the manner in which material was laid out was a guide to interpreting the poem.9

The abbreviations, irregular spacing and line-breaks which were common to a new generation of writers influenced by American-derived ‘open form’ poetry were generally perceived by traditional critics as distracting weaknesses, but such structural arrangements were any- thing but careless or random interruptions to the text. Rather, it was the editorial inattention, or deliberate alteration, which these spatial nuances often suffered that led many writers of this period to have recourse to handpresses. What had been correctly interpreted by the critics was the challenge to the literary orthodoxy that such work represented. The rise of a new activist and contestatory poetics that was intent on, in Robert Creeley’s words, “hammering at the presumptions” [1978] sought to establish itself outside the traditional institutions of literature production.10 In the same letter to Loney, Creeley elaborated on these “presumptions”, expressing the frustration felt by many young New Zealand poets: “it’s as though people are still reluctant to take responsibility for the literal prosody and language possibilities, and won’t for whatever reason read— so use a rather drab and mechanical ‘idea’ of how poems ‘should’ look and move and sound.” Loney clearly echoed these sentiments, opting to take control of the shape of his language: “any variation of margin has auto- matically the effect of producing emphasis, or at the least an interruption, however slight, in the flow of reading. And the lines so varied have got to be able to bear that placement”; he concluded: “I cannot myself see any other function for typographical variation in a poem, than a guide to how the thing is to be read” [Loney-Davidson]. By means of the Hawk Press, he sought to offer an outlet that would both countenance and keep faithful to such writing activities, and thereby challenge accepted notions of what poetry books ‘should’ be.

Production & distribution

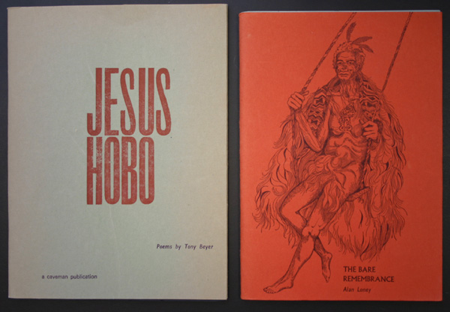

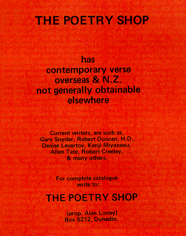

As well as discovering Charles Olson in Dunedin in 1971, Loney extended his involvement in literature into the field of production and distribution. Caveman Press was set up by Trevor Reeves and his brother Graeme as an alternative to the conservatism of existing publishing outlets. Loney helped out by liaising with the commercial printer who printed Stanley Palmer’s graphics in Tony Beyer’s Jesus Hobo and handsetting most of his first volume of poems, The Bare Remembrance. This marked the beginning of a unique involvement with the production of his own texts. He also extended this into distribution by importing predominantly American books of poetry that were “not generally obtainable elsewhere.” Garret Books, or The Poetry Shop as it was later known, operated out of Port Chalmers for over a year, between 1972–4, selling its books mostly by mail-order. In these modest beginnings can be seen the foundations of much of the work he was to do as poet, printer and publisher, and, in many ways, his desire to “extend the discussion”11 of poetics seems to have made the broad scope of his later activities almost inevitable.

Although offset technology had contributed to this generation’s exclusion from printed discourse, the resulting availability of anachronistic but cheap hand presses provided a viable means of bypassing commercial publishers and subverting their authority. When Loney was offered a 60- year-old Arab treadle platen for $400, he seized the opportunity. With $90 in his bank and gifts and donations of almost $1000 from friends and anonymous donors, he moved to Christchurch and began a committed cultural investment in his own free enterprise, explicit in his belief that “Hawk Press will never become a company, nor a commercial venture, and all its books will be designed, hand-set, printed and bound by its present sole human component” [Loney-Jarman].12

Publications

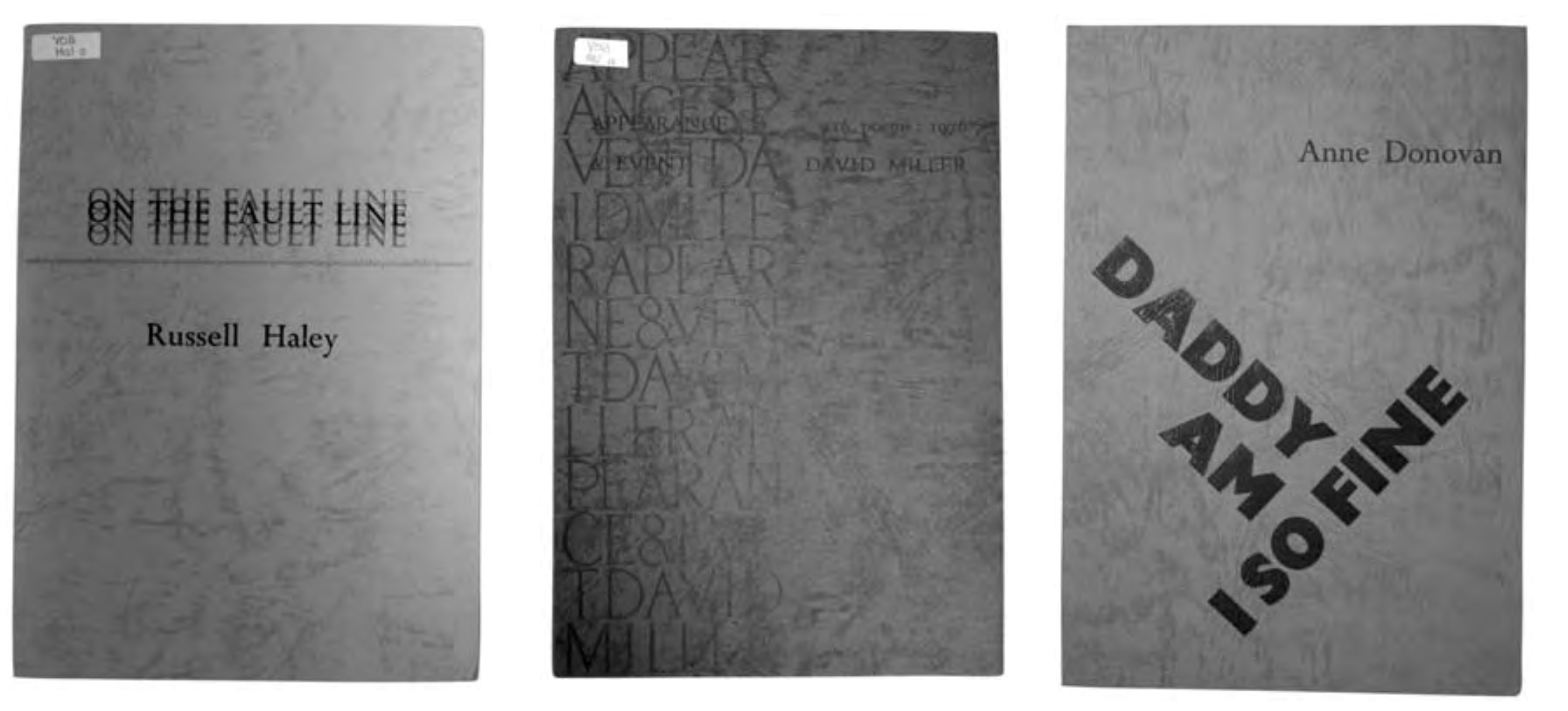

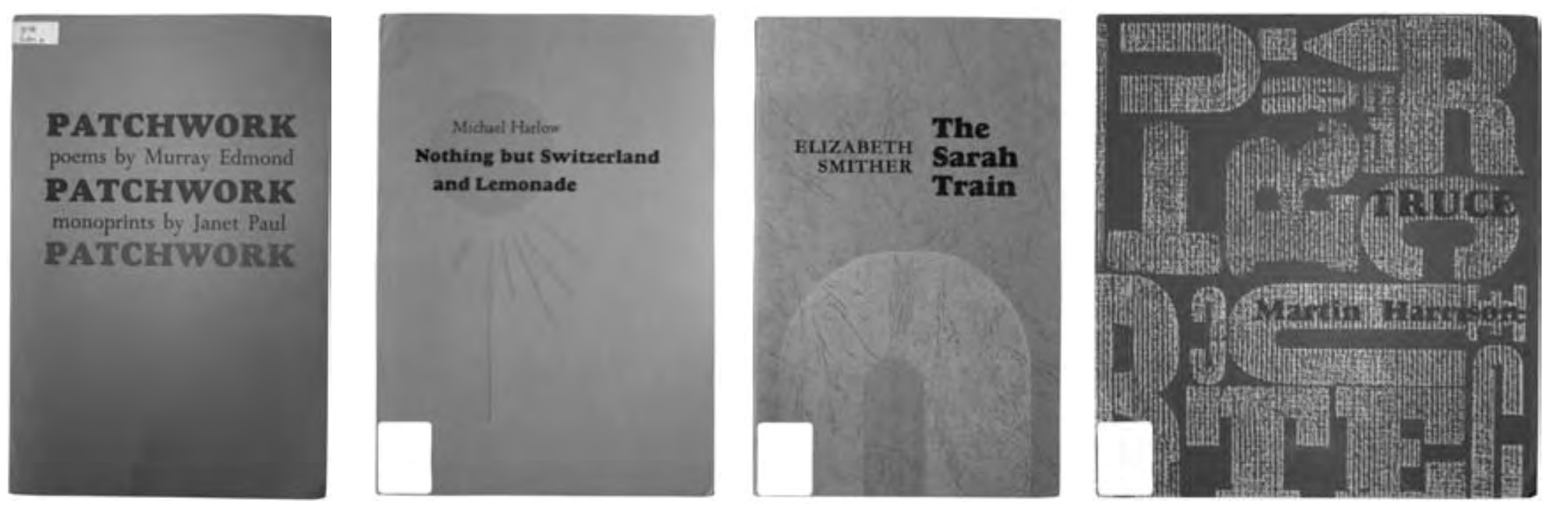

In circumstances reminiscent of Glover almost 40 years earlier, Alan Loney set up his small platen press in a garage at Taylor’s Mistake in what he was later to describe as the “beginning of nine years of a rather obsessive devotion” [‘Flight...’ 1]. The conditions were not conducive to technical mastery as the shed leaked and kerosene lamps provided the only light for working at night. Initially a part-time operation, Hawk Press became full-time for Loney in August 1975, and, amazingly considering its meagre returns, it was to be his sole source of income for the next five years. In the Christchurch Public Library Loney obtained his most practical help in the form of a trade edition of Lewis Allen’s Printing with the Handpress[‘Flight...’ 2]. Armed only with this and the memory of an attractive book of poems by American poet Ed Dorn seen in Wellington’s Unity Bookshop, he set out to publish poets he considered to be worthy and “to print literature in typographic form appropriate to its content” [Loney-Traue 1/78]. Developing the high level of skill necessary to achieve these lofty ideals in this relative isolation was largely a matter of trial and error, but one in which he achieved a considerable measure of success. In this respect, Loney considered jobbing printing not simply a valuable source of extra income, but a stimulating source of design and technical challenges, such was his desire to improve his skills [‘Flight...’ 3]. In general terms, however, the books usually followed a similar formula: the texts were of poetry, printed in Perpetua and Centaur types on machine-made papers, bound in a single signature handsewn into card with a wraparound cover. Nevertheless, this seemingly simple format was to contain a wide range of innovative poetry and typography that defied conventional expectations.

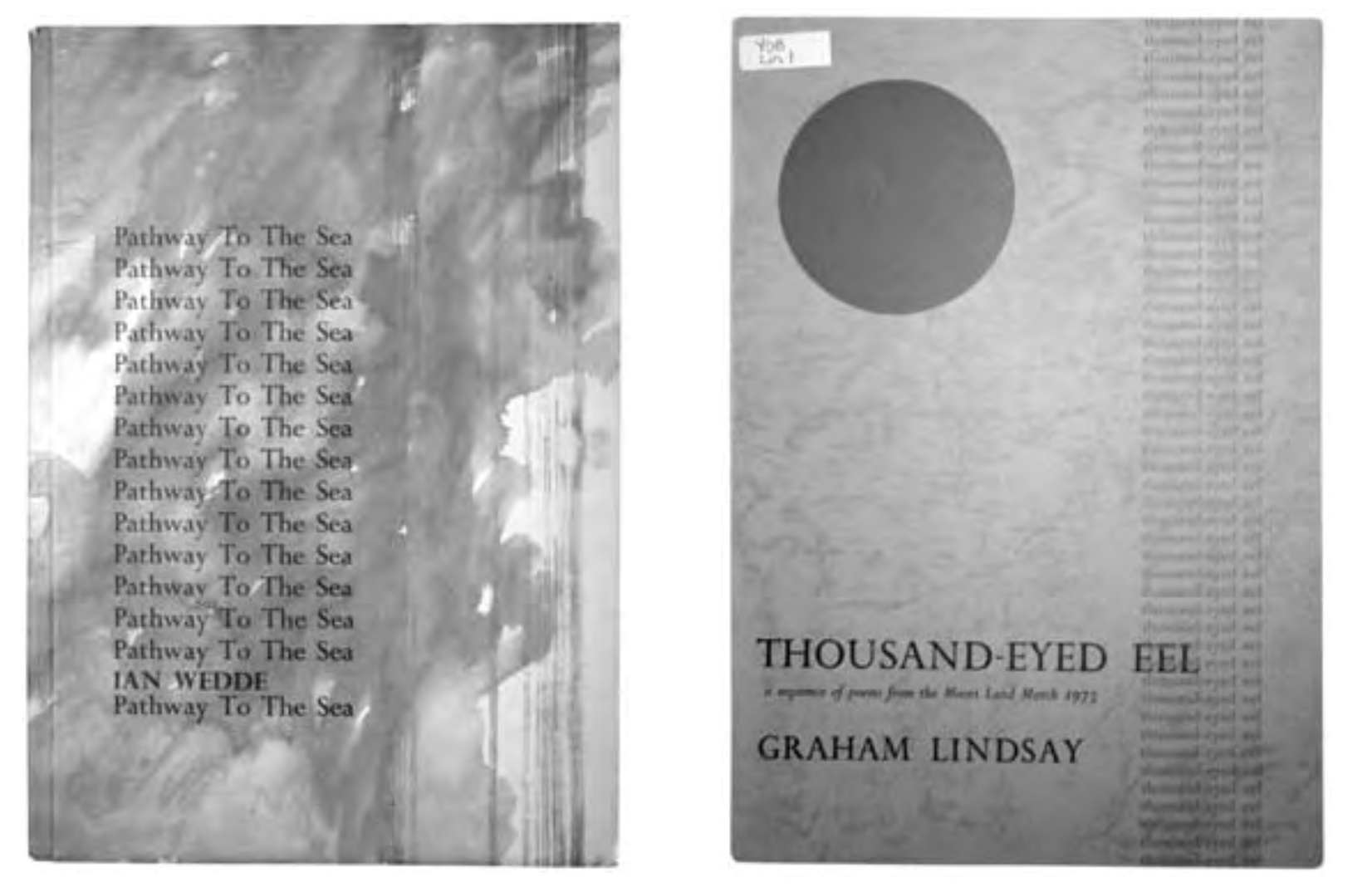

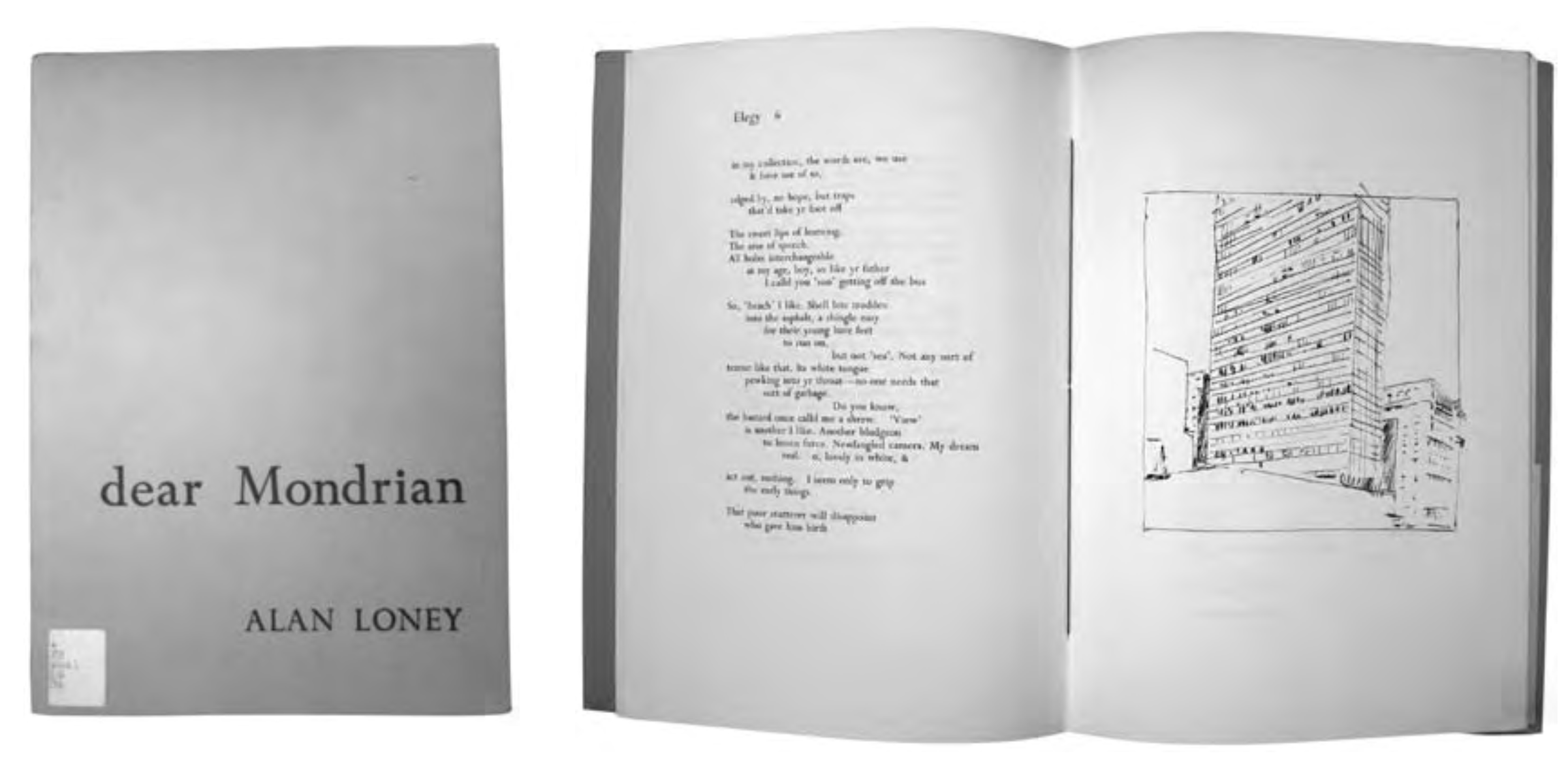

Ian Wedde’s Pathway to the Sea was written in protest at the possible desecration of Aramoana by the proposed aluminium smelter, and was the first of two books produced13 in Hawk Press’s first year. The sympa- thetic cover wash by Ralph Hotere was also the first of many artistic collaborations undertaken by the press, and Loney regarded the book as his most successful typographically of the eight he produced in Christchurch [Coates]. The third book, dear Mondrian, was by the publisher himself and was received, both inside and outside New Zealand, as a very necessary and vital expression of a new poetic. Critic Alistair Paterson wrote in the 1978 New Zealand/Israeli double issue of Pilgrims, “of all the books so far issued from the Hawk Press, however, the most outstanding is undoubtedly that written by the Loney himself. dear Mondrian is plainly a major tour de force which successfully marries techniques and skills borrowed from American writers with an acute New Zealand sensibility” [125]. American source poet Robert Creeley enthusiastically agreed, drawing special attention to the book’s production: “Alan Loney’s dear Mondrian [sic] is work of complex and significant order ‘for New Zealand’ in many senses indeed ... Loney’s mastery at ‘this stage of the problem’ [that is, as physical book] is such that at least a small monument in some unused public square would seem an entirely just reward” [Creeley 467]. While the monument never eventuated, Loney was acknowledged as the co-winner of the poetry section of the New Zealand Book Awards in 1977.

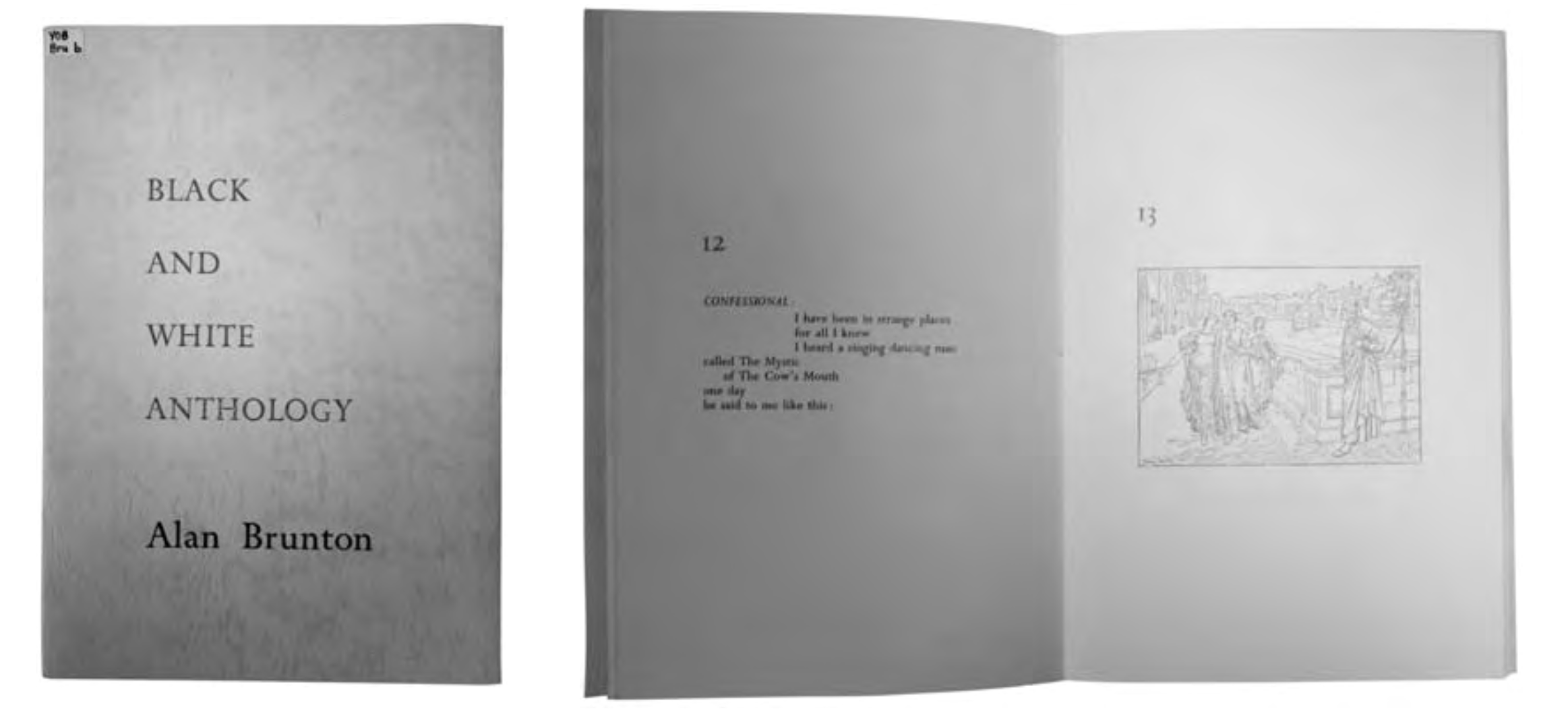

The fourth book to emerge from Hawk Press was Alan Brunton’s Black and White Anthology, which was a design homage to the Edward Dorn book of love poems that had so impressed Loney in Wellington at the very start of his printing and publishing ventures. It was the model for Brun- ton’s book, and all the numbering and colours were the same [Personal]. For his part, Brunton praised the integrity of Loney’s design, acknowledg- ing its amplification of the ideas contained within the text, with one slight reservation: “I really do appreciate the care you gave the text, not just to make a beautiful book but to make a book that in many ways illuminates the text ... It looks beautiful although I shake a little at having to hit all my buddies for $6.00” [Brunton-Loney]. Despite the quality, Loney’s books were inevitably unfavorably compared to cheaper commercially printed books, despite the fact that such a price clearly did not reflect the true labour cost of his craft production methods.

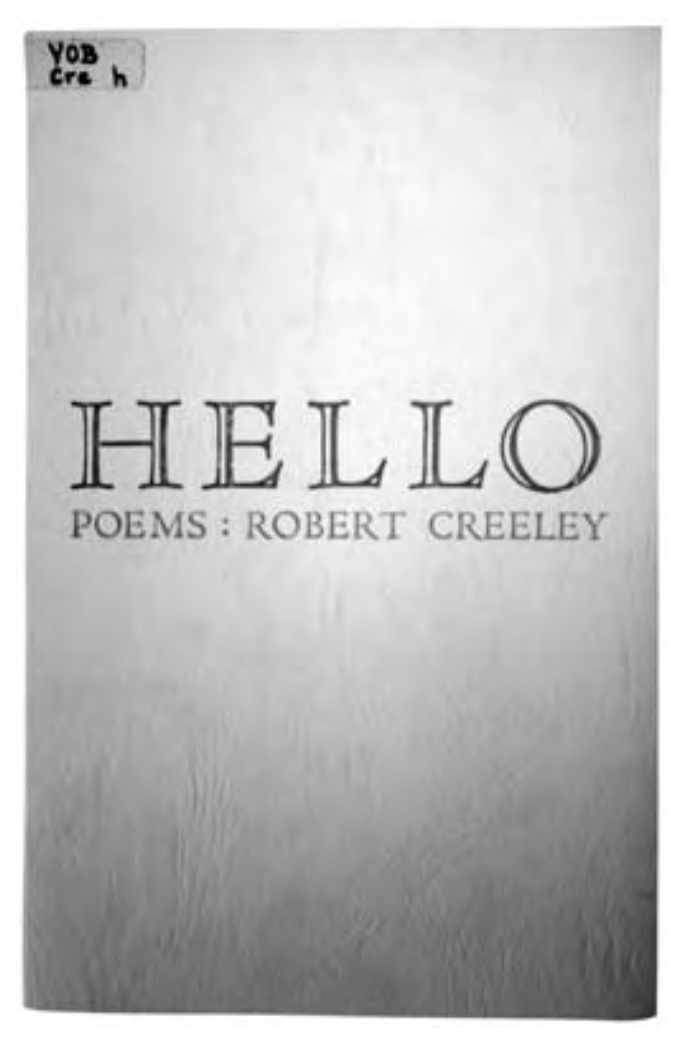

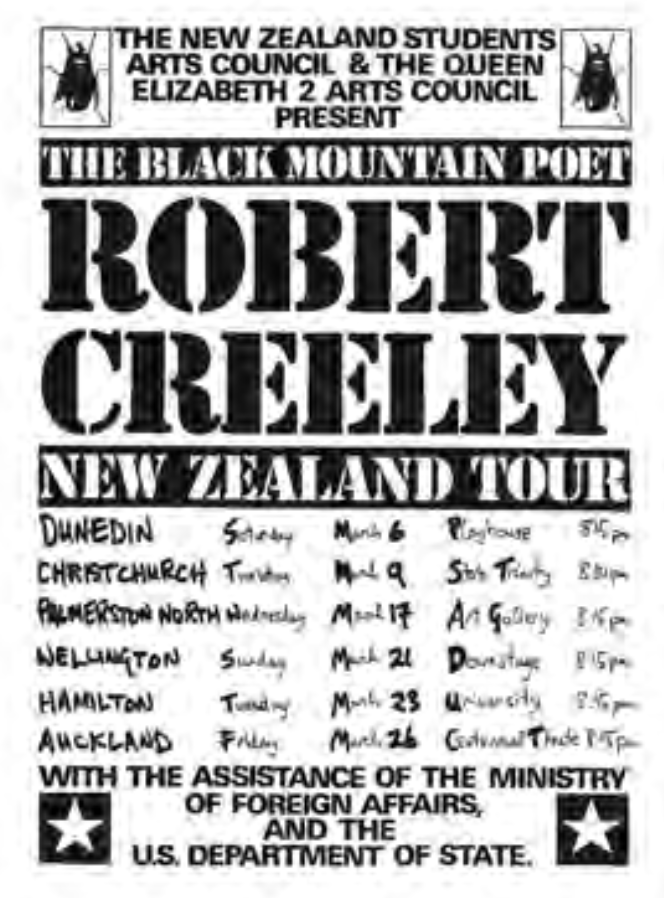

Following Graham Lindsay’s Thousand-Eyed Eel was one of the few books published by Hawk written by a non-New Zealand author. Loney regarded the production of Hello by American Robert Creeley as a “privilege” to print [‘Flight...’ 6]. The poems in this volume were taken from the notebook written during his tour of New Zealand in March 1976, as were the actual physical dimensions of Hello. The exceedingly large (for Hawk) run of 750 copies mostly went to the United States and were sold through Book People in San Francisco. There were also a further 50 limited edition copies, printed on antique laid paper, and numbered and signed by the poet. Creeley willingly waived royalties, enthusing “I feel so well ‘paid’ by having such a lovely thing made of those poems, and that’s really beyond any ‘payment’” [Creeley-Loney 12/3/77]. This publication was something of a coup for a New Zealand publisher, but it seemed to pass largely unnoticed, probably due to a still relatively strong resistance to the supposedly pernicious American influence in established New Zealand literary circles.

Critical intolerance for the writing practices adopted from the United States stemmed from the challenge they represented to the dominant English cultural matrix, which had been firmly embedded at the biblio- graphic level since the Caxton Press established the pattern in New Zealand in the 1930s. The literary institution’s inability to encompass new modes was indicative of a certain degree of calcification, particularly in terms of its critical terms of reference. From Loney’s perspective, this situation was not conducive to a dynamic cultural scene: “Other maga- zines and businesses involve what I call ‘the shouting monad machine’ —where there is no dialogue, and no sense of companionableness—no sense, no genuine active sense, of a community of concern among writers” [Loney-Cooper]. There was a sense that new forms of literary expression, rather than being accepted on their own terms, were simply having outmoded critical concerns imposed on them:“the actual work of these people is not enough or deeply enough, discussed. Any discussion which accepts the need to somehow justify the work of our artists as being acceptable because of some ‘NZ’ character one can attach to the work, is doing something very strange” [Loney-Brown].

The first book of poems for 1977 was Pat White’s Signposts, printed for Michael Harlow’s Frontiers Press and featuring a hand-painted cover by Julia Morison. This was the first of seven printed for other publishers and was a measure of Loney’s growing reputation. On a less optimistic note, the final book to appear from the Hawk Press based in Christchurch was Rhys Pasley’s Cafe Life & the Train: 100 of a total 300 copies were withdrawn from publication because of lack of interest and destroyed [Loney, ‘Flight...’ 8]. However, in a little over two years Loney had produced an impressive—for a one-man, self-taught operation—eight books, which, while not without their faults, show few signs of the novice and more indications of the dedicated craftsman. He had also published a number of poets, like Wedde, Brunton and Pasley, who probably would not have been published otherwise, and certainly not in such a sympa- thetic style. It is a tribute to Alan Loney’s perception that many of these poets subsequently became prominent in the new, more heterogeneous poetry scene that developed in New Zealand in the 1980s, justifying Roger Robinson’s claim that “[t]he perceptive and courageous idiosyncracy of Hawk’s list made publishing into a critical act” [Robinson-Loney]. This revival was due in no small part to the work of a number of small presses, of which the Hawk Press was certainly one of the most significant.

During its time in Christchurch the press consisted of only two fonts— 12-point and 14-point—of Eric Gill’s Perpetua type, along with a small collection of ‘sorts’ from Express Typesetters. Loney described this limited range of fonts as “a measure of as great freedom as it is of discipline,” [Loney-Jarman] but acknowledged the need for improvement with regard to registration and evenness of impression. He applied to the New Zealand Literary Fund Advisory Committee for a total of $700 for repairs to the press and the purchase of type and type-cases, in particular a full range of large-size display types, but received only $200. Never-theless he continued to produce books as a metaphorical journeyman printer based at Paraparaumu (1977–8), Days Bay (1979) before settling in Eastbourne (1979–83), adding a further 22 books under the Hawk Press imprint from Wellington. The poetry books he produced continued to reflect both the freedom and discipline of his limited resources, both material and financial, but despite the similar physical dimensions, demonstrate a subtle dialogue with text, typography and colour. He designed the lettering for David Miller’s Appearance and Event, which was drawn

by his wife Alison, and provided a memorable composition of Joanna Paul’s poems written after the death of her child, Imogen. He also experimented with a series of poetry broadsheets titled Hawkeye and printed for publishers in New Zealand and Australia. However, poetry books could not sustain the press or his insatiable desire to improve the quality of his books.

Increasingly Loney was drawn to the world of international fine press printing through his correspondence with mentors such as Lewis Allen and Sebastian Carter of the Rampant Lions Press. The first of these was The Death of Captain Cook by historian and typographer J.C. Beaglehole, which was published by the Alexander Turnbull Library and was lavished not only with new fonts of Poliphilus and Blado but was printed on damped, high quality handmade paper with leather bookcloth and a felt- lined slipcase. Historical and bibliographical works of this sort were the most sought after subjects in the rarefied world of fine press, and the added institutional authority of the Library only added to its prestige and collectability. However, his next experiment in this field was not so warmly received because of its break with both his own practice and the literary expectations of his subscribers.14 Dawn/Water was a collaboration with poet Bill Manhire and artist Andrew Drummond where “the work grows out of their talk” [Loney-Spanos], and consisted of only the two words of the title, variously coloured reproductions of Drummond’s images, and a rogue letter ‘a’ observed by a lazy fly.

Another collaborative conversation that better fitted with fine press convention took place with Edgar Mansfield (1907–96), one of the finest artist-bookbinders of his generation working in Europe. Born in London in 1907, Mansfield had emigrated to New Zealand in 1911, but returned to London in 1934 for further study. From 1948 to 1964, he taught book- binding and design at the London College of Printing and was the first president of the Britain’s Guild of Contemporary Bookbinders (1955–1968) before returning to New Zealand. The resulting book, 11.2.80 on Creation, and separate loose sheets recollect his remarkable career and reflect on the nature of his creation. It is a just tribute to the rich heritage of the art of the book little known in his adopted country until the appearance of this book.

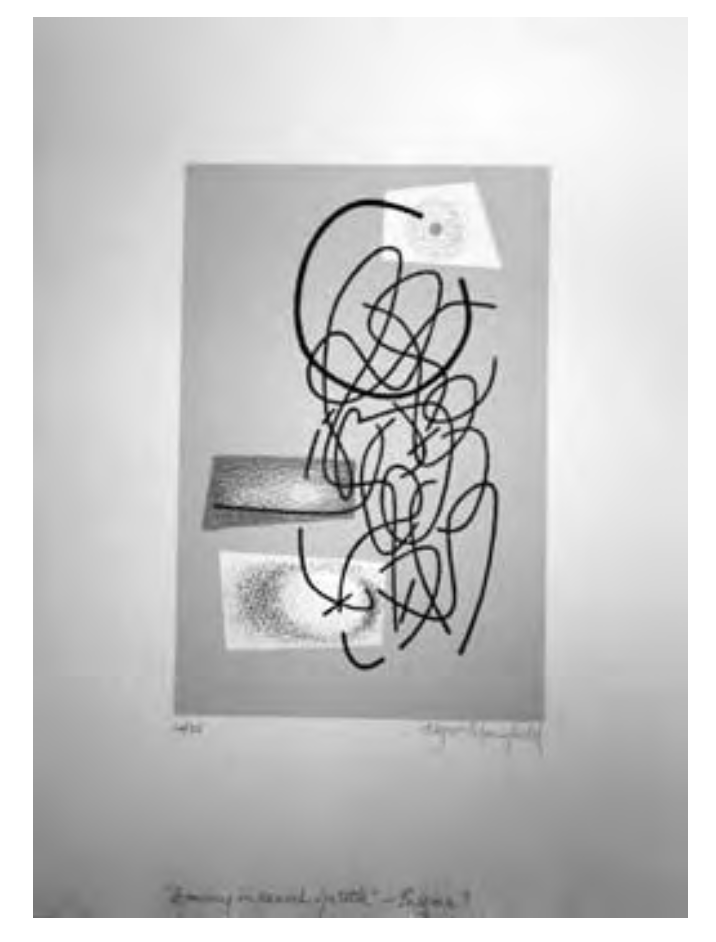

Loney finally had to call it a day in the middle of 1983, his dream of a full- time private press thwarted by the vicissitudes of publishing that had accounted for many others before him in New Zealand cultural history, and most after a much shorter duration and leaving behind a much less impressive legacy. After six years, he had not made a profit from any of the books he had published, and had accrued debts totaling almost $6000 (the majority of this sum had accumulated in the last two years of the press as he had turned his attention to producing fine, limited editions [Loney-Traue 15/8/81]). However, he saved his best for last, letting rip in Squeezing the Bones, a deeply moving and unrestrained eulogy for his father that accommodates his last living moments, his death and his son’s response to his passing. The economy and precision of the language is counterbalanced by an emotionally charged explosion of colour that is evocative rather than descriptive and disrupts fixed meaning, or as Gregory O’Brien put it: “Visual and verbal aren’t aimed at hitting the same register—they create a new, original register”[70].

Craft & control

Alan Loney’s adoption of craft principles in the face of an increasingly industrialised printing and publishing industry enabled him to re-assert control of his creative output and those of a number of writers and artists working at the boundaries of their respective fields. Composing by hand, he came to have a very intimate association with words, literally weighing up the effect and relative importance of each one (and this applied not only to his own writing but to those he published), such that “every word must really count” [Coates]. He brought this careful craft ethos to bear in his typography, effecting subtleties and shifts in language. His paradoxical postmodern private press proved to be a critical act in extending the discussion of poetics and design, increasing the receptiveness to influence and breaking down divisions between the visual and the verbal. However, the demise of Hawk Press was not the end of the book for Loney, as the following selection [see page 94] from his subsequent venture, Black Light, demonstrates, and he continues to remain open to its possibilities for creative and meaningful expression.

Anon, ‘Reading the Fine Print’. Designscape 134, 1981. 12–13.

Brunton, Alan, Letter to Alan Loney. 28 July, 1976. Loney ms. 81–125–5.

Turnbull Library, Wellington.

Cave, Roderick, The Private Press. 2nd ed. New York: R.R. Bowker, 1983.

Coates, Ken, ‘Poet, Printer, Publisher—‘Labour of Love.’’ Press [Christchurch] 3 March, 1977. 17.

Creeley, Robert, ‘Dear Alan Loney’. Rev. of dear Mondrian, by Alan Loney.

Islands 14, 1975. 467–69.

—, Letter to Alan Loney. 12 March, 1977. Loney ms. 81–125–5. Turnbull Library, Wellington.

—, Letter to Alan Loney. 6 Sept., 1978. Loney ms. 81–125–5. Turnbull Library, Wellington.

Jackaman, Rob, ‘A Survey: Introduction’. Landfall 122, 1977. 91–102. Jarman, M., Letter to Alan Loney. 15 Sept., 1976. Loney ms. 81–125–5. Turnbull Library, Wellington.

Lloyd Jenkins, Douglas, At Home: A Century of New Zealand Design. Auckland: Godwit, 2004.

Loney, Alan, Address, Albert Wendt’s Creative Writing class. Audiocassette

held by the author. University of Auckland. 22 Sept., 1992.

—, &, The Ampersand. Wellington: Black Light, 1990. N. pag.

—, ‘Flight of the Hawk.’ Unpublished ms. Copy held by the author.

—, ‘The Influence of American Poetry on Contemporary Poetic Practice.’ JNZL 10, 1992. 92–98.

—, Letter to Lewis Allen. 24 Jan., 1978. Loney ms. 81–125–5. Turnbull Library, Wellington.

—, Letter to Gordon Brown. 18 Dec., 1978. Loney ms. 81–125–5. Turnbull Library, Wellington.

—, Letter to Sebastian Carter. 8 Jan., 1978. Loney ms. 81–125–5.

Turnbull Library, Wellington.

—, Letter to Ronda Cooper. 18 Nov., 1981. Loney ms. 83–220–1. Turnbull Library, Wellington.

—, Letter to John Davidson. 30 Dec., 1977. Loney ms. 81–125–5. Turnbull Library, Wellington.

—, Letter to M. Jarman. 7 June, 1975. Loney ms. 83–220–1. Turnbull Library, Wellington.

—, Letter to Bill Spanos. 9 March, 1977. Loney ms. 81–125–5. Turnbull Library, Wellington.

—, Letter to J.E. Traue. [n.d. Jan., 1978?]. Loney ms. 81–125–5. Turnbull Library, Wellington.

—, Letter to J.E. Traue. 15 Aug., 1981. Loney ms. 81–125–5. Turnbull Library, Wellington.

—, Personal interview. Audiocassette held by author. 23 Sept., 1992.

—, Response to ‘A Survey.’ Landfall 122, 1977. 118–24.

—, ‘Talking with Alan Loney Wednesday 31.8.83.’ Interview with Leigh Davis. And/1, 1983. 39–61.

McGann, Jerome J., Social Values and Poetic Acts: The Historical Judgement of Literary Work. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard UP, 1988.

O’Brien, Gregory, ‘On and around Creation: The Hand–made Books of Alan Loney.’ Art New Zealand 57, 1990–91. 70–72.

Paterson, Alistair, ‘Recent Developments in New Zealand Poetry.” Pilgrims 3.1–2 (1978): 123–28.

Robinson, Roger, Letter to Alan Loney. 30 Nov. 1981. Loney ms. 83–220–1 Turnbull Library, Wellington.

Simon, Herbert A., ‘The Science of Design: Creating the artificial.’ The Sciences of the Artificial. Cambridge, M.I.T. Press, 1996. 111–38.

Footnotes

The article ‘Reading the Fine Print’ and photograph above appeared in Designscape 134, [p12]. ↵

Bensemann and Glover were the co- directors of the Caxton Press; a small, primarily literary printing and publishing house that set new standards in typography and book design inNew Zealand. ↵

See special issue of AbWW 17 Auckland: Writers Group, 2000 dedicated to Alan Loney. ↵

The definition of design applied here is appropriately inclusive—“Everyone designs who devises course of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones” [Simon, 111]. I have adopted a cross-disciplinary Design Studies approach that combines reflection on the theory and practice of design in conjunction with context-relevant studies in other fields—in this case print culture, literature and art. ↵

In the 1930s the Caxton Press and the Group artists in Christchurch shaped a collaborative cultural nationalist programme that was developed in the 1950s through architecture by Group Architects in Auckland and the Architectural Centre in Wellington. ↵

See ‘The Byron of Burnside: Bob Gormack’s Nag’s Head Press’ by Noel Waite in A Book in the Hand: Essays on the History of the Book in New Zealand [Auckland University Press, 2000. 188- 201.] ↵

Loney wrote in reply to Rob Jackaman’s charge that jazz and blues rhythms were “grotesque” [‘Survey’ 100] in New Zealand: “Jazz has been an active part of many N.Z. lives for decades. No-one who has, as I have, been a jazz musician, or been the white boy in a Maori rock and blues group that played the toughest Wellington dance-hall of the late 50s and early 60s, can remain untouched by that experience” [Response 120). ↵

Olson had taught at the experimental Black Mountain College that had included Josef and Anni Albers and Buckminster Fuller amongst its teachers and had its building designed by Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. ↵

Most of the details in this paragraph are taken from an address given by Alan Loney to Albert Wendt’s Creative Writing class at Auckland University on 22 September, 1992. ↵

Jerome McGann’s description of the division in the American poetry scene in the early 1970s applies equally well to the split that was emerging in New Zealand in the same period. He described, on the one hand, an older generationwho produced “a localised verse with moderated surface urbanity,” which “defined ‘social’ and ‘political’ within a limited, even personal horizon,” and, on the other, a post-structural writing which was experimental and generally practised outside the academy, favouring a more oppositional politics [198]. ↵

In an interview with the author, Loney used this phrase in relation to the Book Arts Society, of which he was president and founder, in the sense that he wished to broaden the group’s activities beyond a small group of aficionados into the wider community. In order to do this, he felt that it was necessary to challenge and extend the limits of the field. ↵

While Loney was not a professional designer, Douglas Lloyd-Jenkins has argued for the importance of craft in an understanding of design in the small market of New Zealand. ↵

This was printed in an edition of 200 copies at Wedde’s request, although subsequent volumes, such as Stephen Oliver’s Henwise, were generallyin editions of 300 [Loney-Jarman]. ↵

Some disgruntled subscribers sought their money back, while a more bizarre result was the threat of legal action against the Labour Party who usedan unauthorised copy of the fly for a political flyer. ↵